Rev. Fujio Soin

Rinzai Zen Kencho-ji denomination

Abbot, Doku-on-ji Temple, Yokosuka, Japan

How is a “problem” defined in Zen Buddhism?

The English word “problem” is commonly translated into Japanese as mondai 問題. However, the Chinese characters 問題 consists of: 問 (mon) meaning “to question” or “to continue questioning” and 題 (dai) meaning “a theme” or “a subject”. Problems in business or school exams typically have solutions, correct answers, or methods to resolve them. However, through my work with suicide survivors and individuals with suicidal thoughts, I have realized that problems have two distinct aspects:

1) the visible aspect or problems to be solved. Some problems can and should be resolved, often requiring practical solutions with the help of professionals. Examples include bullying, workplace harassment, domestic violence, stalking, unemployment, financial distress, and legal issues. These are issues where clear steps can be taken to improve the situation and mitigate harm.

2) the invisible aspect or problems to be lived with. Some problems cannot be “solved” in a conventional sense and must instead be faced and lived with. For example, a child who attempts suicide after being bullied at school may later recover through the support of counselors, psychiatrists, teachers, and parents, eventually returning to school. At this stage, people around them may feel that, “The problem has been solved.” However, while the physical wounds may have healed, the emotional wounds may still be bleeding beneath the surface. Such wounds may take years or even a lifetime to fully heal. In some cases, they may never fully disappear. This is what I call a problem that is not “solved” but must be lived with and continuously faced.

In Zen Buddhism, a “problem” is not merely an obstacle but rather a mirror reflecting one’s own state of being. In Western perspectives, problems are often seen as something to be “overcome” or “solved.” However, in Zen, problems are regarded as something to “face” and “learn from.” Suffering in life, known as dukkha in Buddhist philosophy, is inevitable, but rather than simply seeing it as something negative, Zen views it as an opportunity for insight. While minor problems or those that can be easily resolved should be addressed, Zen does not advocate treating every challenge as an enemy to be eliminated. Instead, it teaches us to walk alongside our difficulties, learning from them.

For example, in supporting those who have lost loved ones to suicide or those struggling with suicidal thoughts, the challenges they face are not merely sources of suffering. Rather, by deeply engaging with their pain, they may discover new insights and ways of understanding themselves. The more we try to push away emotions, such as anger, sorrow, or inner pain—treating them as “problems” to be avoided—the stronger they tend to grow. However, by not rejecting them and instead sitting in stillness, quietly observing their true nature, we can grow alongside our struggles. In this sense, problems are not just difficulties to be eliminated; they are opportunities to cultivate understanding and compassion.

What Role Does Mindfulness Play in Problem-Solving?

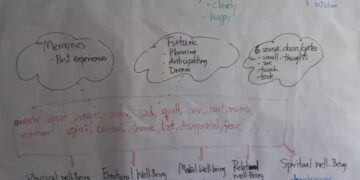

When faced with a problem, we often become trapped in past experiences or overwhelmed by anxiety about the future. Mindfulness helps bring our awareness back to the “here and now,” allowing us to see the problem as it truly is. In Buddhist philosophy, Right Mindfulness (samyak-smṛti in Sanskrit) is one of the practices of the Eightfold Path, a fundamental teaching in Buddhism. The Japanese term shōnen 正念 translates to “right mindfulness”, where nen 念 refers to one’s thoughts or awareness, and shō 正 means to correct or align properly. Our thoughts range from positive to negative, but by consciously directing our attention to the present moment, we can realign our mental state and cultivate a more balanced, harmonious approach. This is the essence of Right Mindfulness in Buddhism.

In my work, I support those who have lost loved ones to suicide or those struggling with suicidal thoughts by helping them develop the ability to observe their thoughts and emotions without being consumed by them. Through zazen (sitting meditation), one cultivates a stable posture and deep, slow breathing, which naturally calms the mind and enables a more peaceful approach to their struggles.

For example, when someone directs intense anger toward us, our instinctive reaction is to respond immediately. However, if we pause and take a deep breath, asking ourselves, “Why is this person so angry?” we begin to see the suffering that lies beneath their emotions. This shift in perspective can dramatically change the situation. Similarly, when confronted with deep sorrow or inner conflict, mindfulness allows us to avoid being swept away by emotional waves. Instead, we can gently observe these emotions, creating space within our heart-minds 心 for greater clarity and acceptance. Mindfulness creates a ma 間—a moment of pause—when facing a problem. This pause opens up mental space, allowing us to respond not with impulsive reactions but with deeper insight and inner peace.

How Does Embracing Uncertainty Enhance Problem-Solving?

In Zen, fuchi 不知, or “not knowing”, does not mean ignorance. Rather, it refers to an open-minded attitude that is free from fixed ideas, allowing us to see things as they truly are. Accepting that we do not know everything is not a sign of weakness but rather an expression of humility and wisdom. In Zen, “not knowing” is considered a form of wisdom.

We often feel compelled to find immediate answers, but true understanding takes time. When we let go of the belief that we must “find the right answer immediately,” our minds become more open, and new possibilities emerge. For example, in the field of suicide prevention and bereavement support, there is no single, definitive “correct” response. Each person’s background and emotional state are unique, and it is essential to acknowledge that we do not have all the answers. Instead of imposing predetermined solutions, we must embrace the unknown, deeply listen to both spoken words and silence. Silence itself can sometimes carry more meaning than words. A person’s facial expressions, body language, and unspoken emotions are also crucial forms of communication.

The night sky may be covered with clouds, but the stars are still there. Instead of trying to force the clouds away, we can simply sit in stillness and wait. Over time, the clouds will naturally drift, revealing the stars once more. In the same way, embracing uncertainty does not mean giving up on problem-solving. It means allowing space for deeper understanding, patience, and the wisdom to see things as they are.

What Does It Mean to “Sit with a Problem” in Zen Practice?

To “sit with a problem” means not to reject or suppress it but to accept it as it is and observe it with quiet awareness. When faced with difficulties, we tend to rush to find solutions, become anxious, or sometimes even try to avoid them. However, in Zen practice, we first learn to be with the problem, to sit with it rather than immediately trying to resolve or escape from it.

In my work with those who have lost loved ones to suicide, I emphasize not the removal of suffering, but the importance of being with suffering. Feelings of loss and deep grief cannot simply be conquered or eliminated. Instead, by gently staying present with them and facing them with quiet awareness, subtle inner shifts begin to occur over time. No matter how painful a reality may be, we must face the truth of what has happened in order to move forward, because the past cannot be changed.

Just as in zazen (sitting meditation), where we observe thoughts and emotions as they arise without clinging to them, we can also learn to sit with the problems in our lives. By doing so, their deeper meaning may gradually become clear. The goal is not to “overcome” the problem but to “be with it”. Through this practice, we find a way to live more peacefully; not by fighting against our struggles, but by coexisting with them.

How Does Zen Encourage Creative Thinking in Problem-Solving?

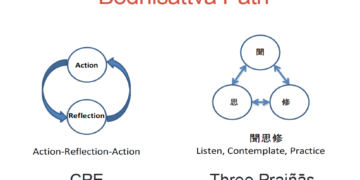

Zen practice fosters awareness of infinite possibilities and cultivates a flexible mindset. We often become trapped in past experiences and fixed ideas, but Zen helps shift our focus to the here and now, opening the door to new perspectives. Practices such as kōan (Zen riddles or paradoxical questions) go beyond logical reasoning and train intuitive awareness. Even in daily life, simple actions like walking meditation or drinking tea can lead to unexpected insights. These insights, often difficult to express in words, form a kind of tacit knowledge that shapes how we navigate life.

In supporting individuals affected by suicide, meaningful realizations often arise not merely from verbal discussion, but from silently sitting together or directing awareness to bodily sensations. Instead of seeking immediate answers through rational analysis, Zen emphasizes moments of deep, embodied understanding; those moments when something “clicks” at a deeper level, beyond words. These realizations often lead to new perspectives and creative solutions.

Rather than rushing to solve problems, Zen encourages pausing, taking a breath, walking slowly, allowing the mind to settle. In that stillness, new ideas emerge naturally. Creative solutions are not something we force into existence; they arise from a quiet mind, like ripples appearing on the surface of a still pond.

An Experience Where the Zen Approach Led to a Breakthrough in Problem-Solving?

Among the people I have supported, there was someone who had lost a loved one to suicide and had been suffering for years from overwhelming guilt, questioning, “Why couldn’t I save them?” Behind this guilt, however, lay not just self-reproach, but also layers of anger toward themselves and others, deep sorrow, and an immense sense of loss. These emotions intertwined, creating an internal storm that kept them trapped in a seemingly endless maze of thoughts. No matter what words were offered, nothing seemed to reach them, and their suffering remained unchanged.

One day, while we were sitting together in silence during zazen (seated meditation), they quietly said, “I just realized… I am breathing right now.” At that moment, I sensed that their mind, which had been living entirely in past regrets and pain, had returned to the present moment. After a long silence, they continued, “I have been blaming myself for so long, but simply noticing my own breath … for some reason, it makes me feel just a little lighter.” They then added, “This pain won’t disappear overnight, but from now on, I want to try taking better care of my own heart-mind and body.”

This experience reinforced for me that in Zen, the essential approach is not about “solving problems” but about being with them, rather than trying to eliminate them. It is not through logic or words that suffering is resolved, but through quietly sitting together, becoming aware of this very moment, and allowing the heart-mind to naturally shift. When this happens, new paths begin to open.

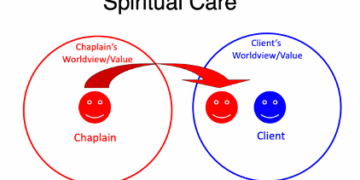

We cannot solve another person’s problems for them. True resolution comes through their own realization. However, by offering gentle presence, listening deeply, and sitting together in silence—or sometimes practicing dōzen together (moving meditation, like tai-chi, see video below)—we can help awaken the peace and insight that already exists within them. In Buddhism, this is known as buddha-nature (busshō 仏性). Just as a seed naturally sprouts and flowers when watered, so too does inner wisdom emerge when given the right conditions. This, I believe, is the true healing power of the Zen approach. Problems may remain unchanged, but the way we perceive them can change. When our minds shift, the way we relate to difficulties also transforms. By learning not to fight against problems, but to coexist with them, we move toward true resolution.