Buddhist Holistic Development & Buddhist Chaplaincy

The Sarvodaya Shramadana movement, founded in 1958 in Sri Lanka by Dr. A.T. Ariyaratne, has been one of the guiding lights of the socially engaged Buddhist movement in the postcolonial and postwar eras. Under Dr. Ariyaratne, it created and systematized a new form of Buddhist-based holistic development. Influenced by the Gandhian values of “self-governance” (swaraj) and “awakening for all” (sarvodaya), it became a nationwide movement by the 1960s and has had seminal influence on a number of Buddhist-based holistic development movements around Asia, principally the Thai Development Monk movement. In these early years, Buddhist monks played a pivotal role in the mobilization of communities to offer the gift (dana) of labor (shrama) in a wide variety of social development activities. The influence and central role of Buddhist monks continued until the late 1990s when the passing of the first generation of these monks created a drastic change. The traditional engagement of Buddhist monks through training and mobilization had difficulties attracting the next generation, yet Sarvodaya continued to keep its Buddhist philosophy and practice at the center of its work, especially for peace building, conflict resolution, and reconciliation. Here in the 21st century, Sarvodaya’s second executive director, Dr. Vinya Ariyaratne, is seeking to recover some important hallmarks of the early movement. Further, while Sarvodaya is known for development work that meets many of the material needs of participants, the entire concept of holistic Buddhist development which they developed includes a balance between outer and inner, material and psycho-social development.

As such, from September 25-26, 2025, Sarvodaya and the Institute of Buddhist Chaplaincy and Counseling (IBCC) under the auspices of the International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB) convened a workshop for monks and nuns on the basic principles and practices of Buddhist chaplaincy and counseling. IBCC, a new initiative founded in January 2025, draws on the network of Buddhist chaplains and counselors that have been emerging in the West and in East Asia since the 1990s. IBCC, itself, emerged out of the Buddhist suicide prevention movement in Japan and the activities of the International Buddhist Exchange Center (IBEC) at Kodosan to document and support this work since 2006. In 2017, IBEC held an international conference on suicide prevention and Buddhist based psycho-spiritual care, which was followed by numerous workshops, conferences, public symposia, and an on-line study group during the Covid pandemic. IBCC is seeking to formalize this work and provide programs and courses in South and Southeast Asia, which up until now have been mostly available only in the West or East Asia. A deeper goal is to nurture the development of an indigenous understanding and form for such Buddhist programs and movements in these areas.

The majority of the participants were 21 monks from the Sarvodaya National Bhikkhu Society, led by Venerable Kuppiyawatte Bodhananda Thero. Ven. Bhodhananda is a longtime member of Sarvodaya who is the founding director of the Mithuru Mithuro Movement, the first and the largest Buddhist based youth drug-rehabilitation center in Sri Lanka. Ven. Bhodhananda, in fact, participated in the aforementioned 2017 international conference on suicide prevention in Japan. His connection with IBEC staff and IBCC director, Jonathan S. Watts, who conducted this workshop, made for a powerful presence during the two days. Among the participants were also a group of six bhikkhunis, led by their senior, Ven. Madulle Vijithananda, who has been a regular participant in INEB activities in recent years. Her temple, the Sakhyadhita International Buddhist temple, has been an important leader in the growing movement to restore female bhikkhuni ordination in the Theravada Buddhist world.

Buddhist Chaplaincy: Ancient Roots and New Streams

The two-day workshop was broken down into two study modules conducted in the mornings: one on Buddhist chaplaincy and the other on Buddhist counseling. While attempting to communicate Buddhist ideas in a Buddhist-poor language, English, the author and workshop leader attempted to define and contextualize the meaning of “Buddhist chaplaincy”. I noted how the Buddha himself was the first Buddhist chaplain, serving monks and laypersons as a death-bed counselor and also a grief-counselor in his famous interaction with the bereaved mother Kisa Gotami. With this basic role model, Buddhists have for millennia engaged in the arts of end-of-life care and grief counseling. However, in the modern world, most of the social roles of Buddhist temples and monks have been replaced by secular institutions, such as modern hospitals and schools. Chaplaincy first developed in the West in the mid 20th century also as a response to the marginalization of religious roles in modern, secular society as well as the crisis of antiquated training systems for religious professionals. Buddhist chaplaincy emerged in the West in the 1990s and has contributed to new styles of chaplaincy, such as meditation-informed “contemplative care”.

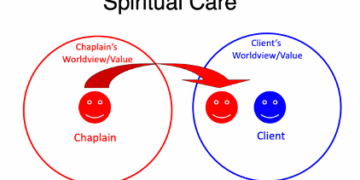

“Chaplaincy” refers to religious professionals of any spiritual tradition who have been trained to meet the psycho-spiritual needs of those suffering in modern, public institutions, such as hospitals, prisons, the military, and so forth. Chaplains serve as compassionate listeners and guides for those suffering and bring peace and meaning to their difficulties. This approach often requires a retraining of skills for ordained persons that are different from their more traditional religious roles as preachers and teachers of truth. In contemporary, multi-cultural societies, chaplains must learn to care for those of other religious backgrounds or for those with no interest in religion. This, again, requires a shift away from conversion and leading others into religious faith, and into the practices of embodied presence and deep listening as each person discovers their own path to truth and meaning.

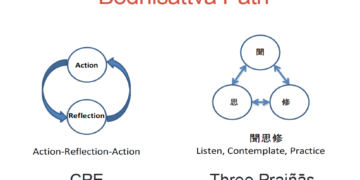

Buddhist chaplaincy has become particularly relevant and increasingly popular in recent years, because the practice of meditation and mindfulness serves as an important tool to develop these skills of embodied presence and deep listening. Buddhist chaplaincy began to develop strongly in the United States in the 1990s primarily in hospitals and prisons. In the early 2000s, Taiwan developed its own indigenous Buddhist chaplaincy program for end-of-life care, which remains an important standard bearer in Asia. In Japan, with a highly secularized society that generally forbids religious persons from working in hospitals, chaplaincy began to grow out of the Buddhist suicide prevention movement in the mid 2000s. It then expanded to disaster trauma after the tsunami and nuclear disasters of 2011 out of which two streams of training in Interfaith Chaplaincy (rinsho shukyo) and Buddhist Chaplaincy (rinsho bukkyo) have emerged. As such, chaplaincy has evolved to encompass many different fields of suffering (dukkha) to include suicide and mental ill-health, disaster trauma, war trauma, and environmental trauma. While Buddhist chaplaincy has a strong inter-relational element focusing on the alleviation of personal suffering, for some practitioners, it also includes developing a clear understanding of structural and cultural issues that are at the root of many forms of suffering. In this way, Buddhist chaplaincy can also be considered a form of Socially Engaged Buddhism.

Buddhist chaplaincy has become particularly relevant and increasingly popular in recent years, because the practice of meditation and mindfulness serves as an important tool to develop these skills of embodied presence and deep listening. Buddhist chaplaincy began to develop strongly in the United States in the 1990s primarily in hospitals and prisons. In the early 2000s, Taiwan developed its own indigenous Buddhist chaplaincy program for end-of-life care, which remains an important standard bearer in Asia. In Japan, with a highly secularized society that generally forbids religious persons from working in hospitals, chaplaincy began to grow out of the Buddhist suicide prevention movement in the mid 2000s. It then expanded to disaster trauma after the tsunami and nuclear disasters of 2011 out of which two streams of training in Interfaith Chaplaincy (rinsho shukyo) and Buddhist Chaplaincy (rinsho bukkyo) have emerged. As such, chaplaincy has evolved to encompass many different fields of suffering (dukkha) to include suicide and mental ill-health, disaster trauma, war trauma, and environmental trauma. While Buddhist chaplaincy has a strong inter-relational element focusing on the alleviation of personal suffering, for some practitioners, it also includes developing a clear understanding of structural and cultural issues that are at the root of many forms of suffering. In this way, Buddhist chaplaincy can also be considered a form of Socially Engaged Buddhism.

Buddhist Counseling

Buddhist chaplaincy generally refers to a range of skills and forms of engagement common to other religions, often described as “pastoral counseling” or “spiritual care”. Buddhist counseling, however, brings in a new template for psycho-spiritual care, which may differ from more theistic forms of chaplaincy and yet is also often at odds with the fields of modern psychotherapy and counseling. Principally, more traditional and institutionalized psychotherapy and counseling have focused on the cognitive mind as the locus for behavioral change. Built on the modernist and utilitarian paradigm of rationality, efficiency, and goal-focused performance, modern therapy has usually over-focused on the individual and lost track of the inter-personal and even trans-personal. While of course there are many exceptions to this generalization, most people across the globe today suffering from mental health issues are diagnosed with bio-chemical and neurological disorders that are treated with prescription medicines and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). Fortunately, a huge shift in this paradigm has begun over the last two decades, in part due to Buddhist influenced therapy models.

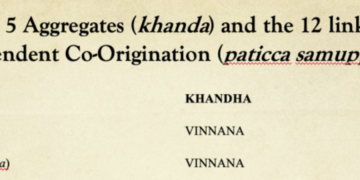

Needless to say, the Buddhist approach to psychological well-being has developed from a different foundation. We could say that the beginning of Buddhist psychology can be found in the Four Foundations of Mindfulness, known as the satipatthana. Once again, we struggle to explain this tradition through English. However, Bhikkhu Analayo’s brilliant contemporary commentary on this teaching explains that “to speak of satipatthana is less a question of the nature of the object that is chosen than of ‘attending’ to whatever situation with a balanced attitude and with mindfulness being ‘present’”.[1] In this way, we are pushed out of conceptual understandings of the Buddha’s teachings as cognitive inputs and are thrust into their practice, in this case, as the Four Ways or Attitudes of Being Mindful (satipatthana). Thus, we begin with the first way of practice in contemplation and regulation of the body (kaya), then secondly, visceral feeling or energetic body (vedana), then thirdly, the mind or cognitive mind (citta), and finally, dhamma, which can be explained as various psychological distortions as well as enlightened states, such as the five hindrances (nivarana), the seven factors of awakening (bojjhanga), and the five aggregates (khandha).[2]

Needless to say, the Buddhist approach to psychological well-being has developed from a different foundation. We could say that the beginning of Buddhist psychology can be found in the Four Foundations of Mindfulness, known as the satipatthana. Once again, we struggle to explain this tradition through English. However, Bhikkhu Analayo’s brilliant contemporary commentary on this teaching explains that “to speak of satipatthana is less a question of the nature of the object that is chosen than of ‘attending’ to whatever situation with a balanced attitude and with mindfulness being ‘present’”.[1] In this way, we are pushed out of conceptual understandings of the Buddha’s teachings as cognitive inputs and are thrust into their practice, in this case, as the Four Ways or Attitudes of Being Mindful (satipatthana). Thus, we begin with the first way of practice in contemplation and regulation of the body (kaya), then secondly, visceral feeling or energetic body (vedana), then thirdly, the mind or cognitive mind (citta), and finally, dhamma, which can be explained as various psychological distortions as well as enlightened states, such as the five hindrances (nivarana), the seven factors of awakening (bojjhanga), and the five aggregates (khandha).[2]

The key point in this sequence in reference to modern psychology is the necessity of beginning with somatic systems, such as breathing and posture, in the first satipatthana. Once these have been “calmed” or regulated, another aspect of what is considered somatic work is attention to various energy systems—such as the nervous, immune, and vagal systems—through visceral feeling (vedana), defined in Buddhism as positive, negative, or neutral feeling. Once these two foundations have been experienced and settled into equanimous regulation, then one can move into cognitive work in both citta and dhamma practices. While mindfulness has become quite popular in contemporary therapy, it has been largely taken out of its context and employed in the service of cognitive-first, performance-enhancement behavioral therapy. One of the reasons that mindfulness practice as well as various forms of Asian somatic practice, such as yoga and chi-gung, have also become popular in modern therapy is the dogged persistence of traumatic response in patients who have endured years of pharmaceutical and cognitive therapy. Why do persons who are highly intelligent and have spent a significant amount of time coming to terms with their traumas still dysregulate in fits of rage, alcohol or substance abuse benders, or days of shut down in bed? It seems, as the Buddha taught, that no matter how much one works with the mind, a foundation of cognitive and psychological health can never be fully established when the somatic systems of body (kaya) and energetic body (vedana) remain dysregulated. The modern response to this problem has been various attempts to regulate these somatic realms with bio-engineering through prescription medicines, whose benefits for most people are increasingly under dispute.

Indeed, new areas of neuroscience, such as Polyvagal theory and interpersonal neurobiology, are rediscovering the truths of the satipatthana by examining how trauma, especially early developmental trauma, is stored not just in the body but in the body’s energetic systems. They are further highlighting the inter-relational aspects of these practices, showing how an individual regulates their body-energy-mind in relation to others (neuroception) and creates a “new, integrated, and emergent whole that is greater than the sum of its parts, emphasizing the synergistic nature of human connection and the co-created nature of the mind and well-being”. This quote is not only a good way to express in modern English the ancient Buddhist teachings of not-self (anatta) and dependent co-origination (paticca samuppada). It also helps to highlight the essential aspect of Buddhist practice which, contrary to many stereotypes, is not found in isolated meditation practice but in connection and relation with others as a “community of practice” (sangha). This was an essential differentiation the Buddha made from the many socially isolated, ascetic hermit traditions of his day, which he also experimented with before his eventual enlightenment. This point again points to a fundamental difference with modern therapy, which, as mentioned, is largely devoted to individual, self-performance enhancement for a newer, better self.

This outline of Buddhist psychology is an important foundation for many Buddhist chaplains today. Satipatthana can often be found best exemplified in modern chaplaincy by Zen practitioners, because there is so much emphasis on the first foundation in proper posture in Zen. From this basis, many Zen chaplains are able to establish a foundation in their “gut” that empowers them to be open to the pain of others without the need to cognitively search for behavioral solutions or to emotionally/energetically over empathize while seeking to “save” others from their pain. As a Zen chaplain in New York City working in end-of-life care explains, “Contemplative care means being embodied … with an inner awareness of how to be with our bodies and ourselves. I find this most meaningful with patients in terms of them opening up and connecting in ways they never imagined.”[3] In Japan, Rev. Fujio Soin, a Rinzai Zen sect priest, has used his years of Zen and tai-chi practice to enable him to deeply attune to those with severe mental illness and suicidal ideation. Using mindfulness training grounded in the satipatthana and not as some form of stress-management, chaplains and therapists can walk the middle path between modern performance enhancement and traditional religious salvation. This practice helps to provide a safe space and allows the carer to be present and bear witness, thus enabling them to sit and listen to stories that have meaning and value, rather than preaching. Such practice welcomes paradox and ambiguity, trusting that these will emerge into some degree of awakening. Finally, this practice helps the other to face life directly and to discover their own truth.[4]

Workshopping

Working with this group of traditional Theravada monks and nuns, the foundational templates of the Buddha as chaplain and satipatthana as counseling made the work of transmitting and translating this material much easier. Further, time was taken to encourage experimentation with new ways of working with traditional teachings. One such experiment was introducing the monks and nuns to the practice of strict posture alignment in Zen. Zen, more properly pronounced as Chan in Chinese, emerged as a hybrid of Buddhist Mahayana practices with already existing Taoist ones in ancient China. This Taoist tradition encompasses the “yogic arts” of tai-chi and chi-gung, which provide the hard science of posture alignment as an essential basis for energetic regulation. These form the basis of the Zen approach to satipatthana upon which sits the “cognitive” practices of the Mahayana Perfection of Wisdom (prajna-paramita) teachings.

For this workshop, I simply used the Japanese tradition of sitting seiza, with legs folded under the body, and the use of ample cushions so that the practitioner does not have to endure the leg pain that can occur for people who have not practiced this way. Seiza offers a much more direct and simple way for one to sink into their pelvic base and straighten their spine, thereby opening the chest for deeper breathing and leading much more easily into regulation of the energetic body (vedana). While Theravada practitioners may discover this wisdom through cross legged practice, it is often not emphasized, and even monks may not regularly sit with a straight back. A number of the participants found this new style quite affable and perhaps felt confident in it as it was presented as a fundamental aspect of the satipatthana. In different sessions, the monks and nuns were invited contemplate the first two satipatthana of kaya and vedana to not only notice the effect on themselves but also investigate how a well-regulated somatic state would empower them to confront the suffering of others as chaplains and counselors.

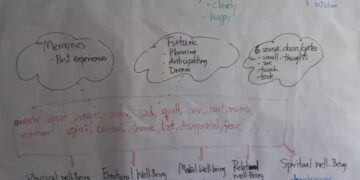

A second contemporary application of classic Buddhist teachings in this workshop was the use of the Four Noble Truths for social analysis and action planning. With the mornings devoted to studying issues in chaplaincy and counseling, the afternoons were spent workshopping on social contexts in which each of the participants are living. As mentioned above, chaplaincy involves social ethics and extending one’s service towards engagement in dysfunctional social systems that form deeper causes of individual suffering. Starting from the 1st Noble Truth of dukkha, expressed again in English awkwardly and incompletely as “suffering” (the “what”), participants attempted to identify the main expressions or manifestations of dukkha in their communities, especially from the standpoints of mental health and inter-relational issues. Common themes emerged as suicide and drug addiction, especially among the young; the crumbling of family systems with domestic violence and adultery being commonplace; and an overall level of high stress as the pace of life has become overwhelming as Sri Lankans chase the dream of “more” through overwork and overconsumption.

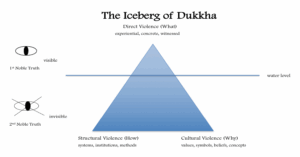

The 2nd Noble Truth proved more challenging to the group as they were exposed to the concepts of Structural Violence (systems, institutions, and methods—the “how”) and Cultural Violence (values, symbols, ideas, and beliefs—the “why”), which are the underlying causes of dukkha often not seen or recognized as “the way things simply work”. The first stage of this part was for individuals to sit alone and contemplate the structural and cultural causes of the dukkha they had identified. However, one group of monks were still teenagers, and many of these monastics struggled to get beyond individual attitudes. Some even fell for the common trap of blaming individuals for their misfortune, such as being lazy or not being educated. This trap is why we call this first matrix of the 1st and 2nd Noble Truths, the Iceberg of Dukkha, because so many forms of suffering are explained as the failings of the individual, especially today in the social taint of mental illness. Religion, in fact, often plays a role in constructing the opaque surface of the water that obscures the gigantic iceberg of structural and cultural violence below. In particular, the misunderstanding and misuse of the teaching of karma in Buddhism has rationalized sexism, classicism, and social injustice in many forms in Asia.[5]

In this way, the individuals and their groups needed to be brought into the wider circle of all participants to expand the range of views and to try to uncover the deeper roots of dukkha. In this process, a key structural foundation of Sri Lanka’s heavy emphasis on consumer capitalism was discovered in the adoption of neo-liberal economic systems in the late 1970s. It was also pointed out that that the horrific civil war exploded in full form soon after in 1983, another causal link to be explored. Within this system, there has been a transformation of the traditional Sinhala Buddhist value of “contentment” (santutthi) into the present culture of “more”, which is driving Sri Lankans to over work, over consume, and become increasingly emotionally erratic. Through this larger group process, participants became much clearer as to how to use this system of analysis, and then returned to their small groups to work on specific analyses of issues they had identified.

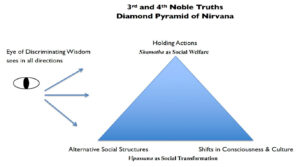

Building on this work, participants in the second afternoon worked on creative solutions through the 3rd and 4th Noble Truths re-envisioned through Joanna Macy’s Three Dimensions of the Great Turning: 1) Holding Actions, emergency short-term actions to address the critical suffering witnessed in the 1st Noble Truth, 2) Transforming the Foundations of our Common Life or Alternative Social Structures, and 3) Shifts in Perception and Values/Consciousness and Culture. It should be noted that Macy, herself, was strongly influenced by the Sarvodaya movement, where she worked for a year studying Buddhist community organizing. Again, as a way to contextualize and communicate these ideas within Buddhist, and especially Theravada, teachings, Holding Actions were explained as a kind of social shamatha meditation practice. Shamatha is “calming” meditation, which allows the energetic system to regulate so that the deeper work of vipassana or “insight” can take place, rooting out the deeper causes of dukkha. Holding Actions are, thus, various kinds of emergency work to help those in suffering—such as, telephone hotlines for the suicidal, soup kitchens for the homeless, protests to prevent the re-start of nuclear reactors—which “hold” the damage being done at bay but do not root out the core causes of social injustice. The other two dimensions are the work of social vipassana, such as creating new value systems not based in greed-anger-delusion (such as in consumer capitalism) but rather based in sharing (dana), contentment (santutthi), sympathetic joy (muditha). The structures that emerge out of this culture empower individual citizens to act with critical insight and agency while building a collective (sangha) that balances the middle way between selfish individualism and mindless collectivism.

Further exposing the potholes in modern education, participants in this workshop also often struggle in these stages of the process. In the 2nd Noble Truth, the barrier is usually critical thought, in which students raised on rote learning still struggle. The barrier in the 3rd and 4th Noble Truths is creative thought, for which even those who have had elite educations struggle as they possess overly critical, analytical minds. In this way, the practice of the social Four Noble Truths does not differ from its practice on an individual level. One must constantly revisit the first step, the 1st Noble Truth of dukkha, re-experience and reconsider it; deepen one’s understanding of causality in the 2nd Noble Truth; and slowly, through an emancipated consciousness from considering causality—the foundation of the Buddha’s final awakening—emerge into a new vision of society and the steps needed to get there.

Obviously, the Sarvodaya Sangha was not going to arrive at such major breakthroughs in one afternoon of working on this stage. Still, through the presentation of numerous case studies, new creative ideas began popping up. For example, Japanese Buddhists have used cafés, either within temples or off site, as a way to create safe, non-judgmental places for people to re-connect and begin to express their suffering. Such cafés have been established in refugee centers for victims of the 2011 tsunami and nuclear incident and in spaces at city hall centers in small towns for those struggling with mental illness and community collapse. One of the groups in this workshop envisioned a “Take-a-Break” café for young people in the temple, where they could get free snacks and drinks but would have to turn off their phones while in the café and allow for face-to-face communication. This is a simple sort of Holding Action to get young people away from the toxic culture of social media, but can eventually lead to an alternative social structure, a place in the temple where people can rediscover humanity and enjoy just hanging out with no agendas to be “someone” or “something”. Another initiative envisioned off of this café is an educational space where adults can join young people in learning about healthy parenting, healthy family life, and the healthy use of technology. Still, the focus of the first step is seen as something enjoyable, free, and just for young people as the first targets of a suffering society.

Steps Forward

The Sarvodaya National Bhikkhu Society has a history of some forty years focusing on not only development for basic human needs but also spiritual values, another basic human need. Their focus going forward is to train monks in various social roles for rural leadership. In this way, many of the core values and mechanisms of Sarvodaya remain a focus for the group, such as building a cooperative society through education and micro-credit economic systems. Two weeks earlier, this author facilitated a workshop for a different group of monks and nuns on adopting the principles of rural-based Sarvodaya development work to urban contexts under the guidance of a Japanese priest who has taken these principles and used them in urban Tokyo. This initiative was largely supported by the INEB Eco-Temple Network and the Japanese and Sri Lankan chapters of INEB. As such, I challenged the group to also consider how they can integrate this work into the growing urban centers of Sri Lanka, where Buddhists have struggled to adapt as well as to confront the new kinds of problems many identified in their group work.

As mentioned, there was a group of six bhikkhuni participants not directly working with Sarvodaya. Three of them had, in fact, participated in this earlier workshop on applying holistic Buddhist development to urban environments. In this way, some of them were a step ahead of the monks. Ven. Vijithananda, as the senior representative of the group with some years of experience in community work, outlined the present activities and goals of many Sri Lankan bhikkhuni, who now number up to 4,500. Many operate Sunday schools and Montessori schools in their communities. They also provide an important new role in Theravada Buddhist society by providing a female monastic voice for community women to share difficult issues, such as domestic violence, which they may be hesitant to share with monks who often still maintain patriarchal attitudes. In this way, this new generation of Buddhist nuns have begun building bridges with female leaders from other religions in Sri Lanka. With a common platform in the concern for gender and related issues, these women are becoming natural peacemakers crossing over ethnic and religious divides, which has led to so much violence since Sri Lanka’s independence in 1948.

In conclusion, this workshop should result in fruitful follow up as a foundation of cooperative work has been growing in Sri Lanka over the last decade through the work of INEB and many partners within the country, including Sarvodaya. A previous INEB initiative called Sangha for Peace has worked on the building of holistic peace through intersectionality, that is, the combination of numerous issues in an integrated whole. The work of the bhikkhuni on gender and inter-religious peace is one such example. The connecting of IBCC on chaplaincy and counseling issues with Sarvodaya’s focus on rural development, combined possibly yet again with the INEB Eco-Temple network, presents another great potential for integrated work.

Jonathan S. Watts (October 12, 2025)

[1] Analayo, Satipatthana: The Direct Path to Realization. (Buddhist Publication Society 2003), p. 30.

[2] Analayo, Satipatthana.

[3] Watts, Jonathan S. & Jin, Hitoshi, “Contemplative Engagement: The Development of Buddhist Chaplaincy in the United States & Its Meaning for Japan” (November 2015). https://jneb.net/japan/rinbutsuken/contemplative-engagement1/

[4] This definition of contemplative care is provided by Rev. Jennifer Block, former Bereavement Manager at Zen Hospice Project and Co-founder of the Buddhist Chaplaincy Training Program at the Sati Center for Buddhist Studies. In Giles, Cheryl A. and Miller, Willa B, eds. The Arts of Contemplative Care: Pioneering Voices in Buddhist Chaplaincy and Pastoral Work. Boston: Wisdom Publication, 2012. p. 7.

[5] Watts, Jonathan S. ed. Rethinking Karma: The Dharma of Social Justice. Bangkok: International Network of Engaged Buddhists, 2014.