Special Seminar #2 with Rev. Joan Halifax

Founder of the Upaya Zen Center Being With Dying Program

April 22, 2019

In our ongoing work for suicide prevention and psycho-spiritual counseling at the International Buddhist Exchange Center (IBEC) of the Kodo Kyodan Buddhist Fellowship, we were truly blessed to host Roshi Joan Halifax for her second seminar on April 22, 2019, a follow-up to her first event at our Kodosan temple last December in Yokohama.

At this seminar, we welcomed Buddhist priests and other religious professionals working to develop caring skills in the context of the traditional forms of training within their own denominations. We also welcomed those in the medical and caring professions who are also searching for inner resources for caring in the context of present secular forms of medical care.

In our previous seminar with Roshi Halifax in December of last year, we surveyed the landscape and contexts of suffering in Japan today, especially the high levels of psychological suffering. We also examined the various forms of engagement of Japanese religious professionals in this suffering and the challenges of training people to serve as compassionate listener-guides or “chaplains”—in Japanese often called rinsho-shukyo-shi 臨床宗教師 or in the Buddhist context rinsho-bukkyo-shi 臨床仏教師.

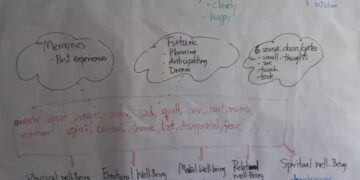

In this second seminar, we explored more deeply with Roshi Halifax these challenges of engagement and compassionate care, principally through Roshi Halifax’s work with “edge states”. These “edge states” are emotional qualities that most religious based caregivers would recognize as essential to develop at a high level, such as: altruism, empathy, integrity, respect, engagement, and compassion. However, in her new book, Standing at the Edge, Roshi Halifax describes the pitfalls and traps of becoming overly immersed in such states, which leads to a variety of damaging behaviors to both the receiver of care and the caregiver.

The first of these states is altruism, which she illustrated in the life stage of a mother octopus who after giving birth, offers her body as food for her children, slowly dying as she is eaten away providing for her newborns. This may be a touching example of altruism in nature, yet Roshi Halifax pointed out that if the ego gets in the way of such acts, the well being of the caregiver or those around them, like family, will lead to physical and emotional exhaustion. Thus, it is essential to see when we go over the boundary from healthy to pathological altruism. The line between these two states can feel unclear, especially if someone dies in the act of trying to save another and causes collateral damage, like leaving his or her own children orphaned. In this way, one has to ask, “What is the question or motivation behind the act?” If there is an attachment to becoming a good person or arriving at a desired outcome, aggression and violence can be directed at the other as well as a neurotic pattern of self-victimization. True and healthy altruists are not looking for personal gain, but do so naturally—for example, one hand will naturally take care of the other when it gets injured rather than contemplating the value of doing that. One effect of the practice of meditation is enabling one to see the connection between others’ suffering and our own suffering, and hence realizing the connection of how care of others is also care of self. In her book, Standing at the Edge, Roshi Halifax also speaks about the process of Not-Knowing, Bearing Witness, and Compassionate Action as a practice for developing authentic altruism.

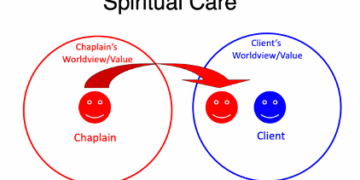

The second state is that of empathy. Empathy means to be in physical, emotional, and mental resonance with another. Physical or somatic empathy is the act of touching another compassionately while caring; emotional or affective empathy is creating an emotional connection with another; mental or cognitive empathy is the act of looking through the eyes of another to see their perspective. The shadow side of empathy is over identification and the loss of self-reference, which can result in the loss of moral and ethical judgment. This is seen in how perfectly moral people in Germany began to view the world through Hitler’s perspective, losing their own moral compass and eventually supporting his horrific policies. Thus, while being in resonance with another, we must also maintain a meta-cognitive perspective that recognizes we are not that person with whom we are in resonance. From a meditative standpoint, this is the development of what Roshi often states as maintaining “a strong back with a soft front”. The “soft front” is the expanding of subjectivity to include all beings, i.e. interbeing; while the “strong back” is the equanimity or emotional balance in the midst of difficult and complex conditions.

The third state is that of integrity. Its shadow side is moral suffering, when we harm ourselves or harm others. This shadow side consists of: 1) moral distress, which arises during a moral dilemma; 2) moral injury, which happens after taking part in or allowing gross acts of harming that result in the feeling of shame and guilt and often suicide in the case of perpetrators of violence; 3) moral outrage, which is a mix of anger and disgust when survival is threatened in the case of victims of violence; and 4) moral apathy, which is when we consciously or unconsciously do not react to moral trespass, as often happens to those in positions of privilege. Mind training and meditation are also essential here to allow suffering to enter the conscious mind and to be able to discern between these subtle states. Roshi Halifax taught the group a basic approach to meditation of gathering one’s attention on the in breath and sinking awareness down into the body on the out breath. In this way, we may expand our awareness through discovering how our mind, heart, and body are reacting to a situation. A feeling of gratefulness can develop from this expansion of inquiry and perspective, from which we may more fully dedicate ourselves to observing the basic vows of non-harming—such as the five Buddhist precepts.

The fourth state is that of respect, which is the holding of others in high regard. Its shadow is disrespect, such as disparagement and bullying. It also includes horizontal hostility, which is disrespect between peers, as well as vertical violence, either commonly in top-down power relationships like teacher to student, but also in bottom-up ones like a patient who bullies a caregiver. In Standing at the Edge, Roshi Halifax speaks about the skills needed to restore misaligned power relationships through mindful awareness, such as not taking things personally or making assumptions; maintaining proper internal and external boundaries; and making as well as renegotiating agreements. She also speaks of the practice of exchanging self with other—as outlined in Shantideva’s Guide to the Bodhisattva Way of Life—to deepen respect, while nurturing wisdom and strengthening resilience when disrespect does occur.

The fifth state is that of engagement, and its shadow side is burnout. Burnout can happen when we do not maintain proper boundaries, get involved in toxic environments, participating in morally questionable acts, and lose our sense of meaning and purpose. In Standing at the Edge, Roshi Halifax reminds us of the Buddha’s fundamental teaching of Right Livelihood as part of the Noble Eightfold Path towards nirvana. From this basis, she speaks about the concept of “work practice” and “no work practice” in which we close the gap between our desired outcomes and efforts to achieve them. In Zen practice, she has learned the art of “actualizing the Way in everyday life” (無上道の体現) where every act is as important as any perceived goal or result of it.

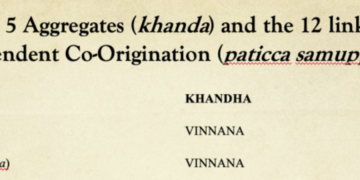

In conclusion, Roshi Halifax emphasized how all these states are interconnected. While meditation is important in being able to suddenly shift one’s mental state while in the field, she explained that compassion is essential in transforming all the shadow sides into their enlightened counterparts—and this, compassion, is the sixth edge state. When we are not able to actualize it, we tend to think that we have failed and are falling over the edge. But, of course, we always learn more from our failures than our successes. Dogen called this the practice of “continuous failure” or “continuous mistake”, and coming back from our failures is what builds character. Compassion is the lever that transforms the negative edge states, because it is made of elements necessary for our state of presence as follows: 1) it cultivates “attentional balance” for clear seeing; 2) it cultivates emotional balance and pro-social qualities; 3) it cultivates moral sensitivity to perceive and moral nerve to take action; 4) it also cultivate deep ethics; yet all of this is not possible without insight which is why compassion is interdependent with wisdom. Compassion has also been found to boost our immune system, leading to longevity, and to elevate our moral awareness. Buddhist practices to cultivate compassion can be done on the basic level with a specific object of compassion in mind. It can also be cultivated conceptually through insight by meditating on the Buddha’s core teachings of impermanence and dependent co-arising. However, the highest stage of cultivation is compassion that is cultivated with no object, which is unconditional or non-referential compassion without bias and is always ready to act appropriately in the moment.

In the middle of this presentation, Roshi Halifax had the participants break into small groups for a discussion on these edge states, and then welcomed them back for a more interactive circle of conversation among our group of 40 participants. Roshi Halifax’s ability to weave in an incredible variety of fields—not only Buddhism and psychology, but also medicine, sociology, anthropology, and even zoology—offered a kind of fully integrated, engaged Buddhism that provided many of the Buddhist priests in attendance a whole new perspective on updating their traditional teachings and practices to contemporary society. This is an inestimable gift of insight as not only Japanese priests, but also Buddhist monks in many other traditional Asian contexts, are struggling to redefine their roles in the 21st century. From the standpoint of the more secular caregivers in attendance, the depth of insight and practical methods that Buddhism offers those in caregiving professions is a resource that cannot be underestimated. Developing skills and “yogas” to become resilient in the face of persistent suffering as well as to be able to transform the shadow states that arise in such work is a precious resource that Roshi Halifax’s teachings offer. We hope to see her again in Yokohama on her next trip to Japan … to be continued.

Report by Jonathan S. Watts, reference notes provided by Nathan Michon