Special Seminar with Rev. Joan Halifax

Founder of Upaya Zen Center Being With Dying Program

December 17, 2018

Amidst a society immersed in a myriad of suffering, what can Buddhism do to confront the suffering of individuals? To answer this question, the International Buddhist Exchange Center at Kodosan hosted a special seminar on December 17 with American Zen teacher and medical anthropologist Roshi Joan Halifax on the theme “Understanding the Interconnectedness of Personal and Social Suffering through Engaged Buddhism”. The event was co-sponsored by the Sophia University Grief Care Institute with cooperative endorsement by the Tohoku University Department of Practical Religious Studies and the Rinbutsuken Institute for Engaged Buddhism—thus bringing together the three major professional, psycho-spiritual care training centers in Japan. 45 participants attended from a variety of related backgrounds ranging from those providing spiritual care for the suicidal, terminally ill, and their families to Buddhists involved in disaster relief to those involved in medical welfare and finally leaders in related research fields. With Roshi Halifax and Kodosan President Shojun Okano leading the discussions, participants offered viewpoints on the issues and problems of supporting those in society who are suffering.

In recent years, a variety of initiatives by both Japanese Buddhist individuals and groups to take on serious social problems such as poverty, isolation, and suicide have emerged. In 2011, especially, a number of acclaimed activities which transcended sectarian and religious divisions were initiated to support victims of the eastern Japan triple disaster. These activities led to the establishment of new programs to train “Buddhist chaplains” (rinsho-bukkyo-shi) and “religious chaplains” (rinsho-shukyo-shi) to care for the psycho-spiritual well-being of people in disaster areas, medical facilities, welfare facilities, and other public institutions.

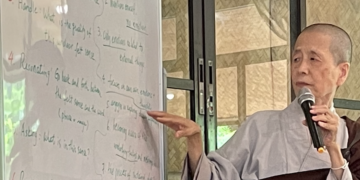

Rev. Okano in his welcoming comments to the group reflected on the shallow history in Japan of cultivating persons to engage in the suffering of the people, noting, “I would like to ask of those of you who have many years of experience, as we move forward, what is the desirable form of religious based activities to develop; what are the key problems to face; and how can we overcome them?” After each of the participants in attendance introduced themselves, Roshi Halifax led the inquiry by reflecting on her experiences as a pioneer in psycho-spiritual care in the United States. With over 50 years of experience working in terminal care, prisons, and other fields, Roshi Halifax explained, “I have been teaching meditation as a means for people to overcome the suffering of isolation and depression in facing death as well as supporting medical professionals to develop the mind of compassion as the basis for their care of patients.” In this way, she explained that with the purpose “of healing the illness of society through healing the minds of individuals, I would like to cultivate a relationship with you all here to develop a community imbued with love and the skills to transform the suffering that is going on now in Japan.”

The Illness of Society

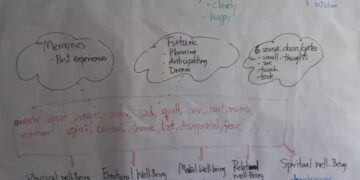

To begin with, everyone was asked to think about what are the current forms of “suffering” (dukkha) that Japan is facing and what kind of people are in need of psycho-spiritual care. A wide variety of answers came from the audience, such as for the first question: the suffering caused by natural and man-made disasters, discrimination, alienation based on different sexual preference and gender ambiguity; and for the second question: hikikomori, alcoholics, victims of domestic violence, and bereaved families of the suicidal. Rev. Okano pointed out that all this suffering could be divided in three basic categories: 1) the fundamental dukkha related to birth, aging, sickness, and death; 2) the dukkha brought about by our own personal feelings and thoughts; and 3) the dukkha brought about by social structures, such as prejudice, discrimination, and social inequality. He further pointed out that the wounds of World War II have not been healed. The society that soldiers came back to after being at war and living in an environment where killing people was a casual thing had completely changed. They experienced great suffering in not being able to speak with family members about the terrible things they had seen and done. He defined this as, “The Japanese problem which lingers deep in our subconscious concerning the many things that our government did during the war that have not been re-examined.”

The Causes of Suffering

Continuing on with the process of inquiry, the conversation turned to the root causes of such social suffering. The participants identified issues such as: indifference or moral apathy, lack of creative imagination, social pressure and oppression, a deep-seated neurosis around the drive for excellence, the tendency to suppress negativity, and the fear of being ostracized. A variety of reflections were then exchanged, such as: “It is not just problems with our culture and values. There are also structural problems, such as death from overwork (karoshi) and the inequalities that arise from capitalist development because of the overemphasis on economic growth.” Roshi Halifax then emphasized the importance of caring for the suffering that is not seen noting that, “As Rev. Okano pointed out in his comments on World War II, a ‘moral apathy’ has emerged from the sense of shame and self-loathing that came from the compromising of people’s values, and a variety of co-dependent or addictive behaviors have emerged from the turning away from this suffering.”

From the Field of Practice

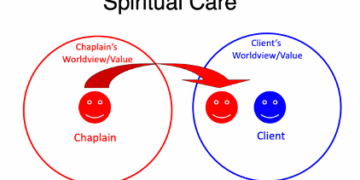

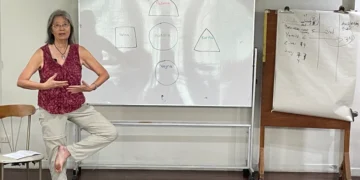

The field of inquiry included presentations by representatives of three organizations training people to provide psycho-spiritual care in a variety of fields such as medicine, social welfare, and education. Prof. Kenta Kasai of the Sophia University Grief Care Institute explained that in their program, “We are concerned about caring for the suffering that comes from the varieties of grief in facing the death of someone important” as well as “understanding other kinds of pain from first facing one’s own grief as it relates to socially constructed grief.” Rev. Taio Kaneda, a Soto Zen priest who has been practicing deep listening with those traumatized by the 2011 tsunami in northeast Japan, then spoke about the background and meaning of the “religious chaplains” (rinsho-shukyo-shi) training course established by Tohoku University and its gradual expansion. In terms of doing work in the public sector, he emphasized the need for deep listening in order “to understand the culture and spiritual climate of the so-called non-religious character of Japanese, which in actuality has been confused for a subtlety of religious sentiment; and to cultivate people who can listen to others without imposing their own values on them.” Finally, Jonathan Watts, a Research Fellow at the Rinbutsuken Institute for Engaged Buddhism (as well as at Kodosan’s International Buddhist Exchange Center) spoke about the need for chaplains to not only provide care and support for patients and their families but also for medical professionals as well as taking on the problems of structural violence that exists in institutions and social systems. Finally, Roshi Halifax asked, “So how can we serve those in suffering?”. Some of the responses that followed were: “empathize with their ignorance and moral apathy”; “listen deeply with a mind of compassion”; “make contact with a proper sense of boundaries and do not become too eager to help”; “it’s important to continue to search for the kinds of values that provide care to the person right in front of us as a one to one connection beyond the role of an expert.”