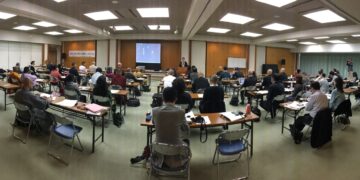

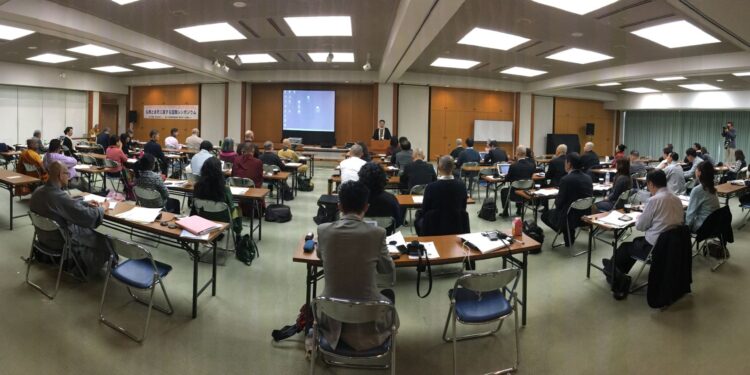

In 2006, one of the co-founders of IBCC, Jonathan S. Watts, began working simultaneously on end-of-life care and suicide prevention at two different Buddhist institutes in Japan. The former with the Jodo Shu Research Institute (JSRI 浄土宗総合研究所) lead to a major publication in Buddhist end-of-life care around the world entitled Buddhist Care for the Dying and Bereaved. This research was then funneled into the establishment of Japan’s first specifically Buddhist chaplaincy training institute in 2013 at the Rinbutsuken Institute for Engaged Buddhism 臨床仏教研究所. The latter with the International Buddhist Exchange Center (IBEC 国際仏教交流センター) formed part of the building of a nationwide network of Buddhist suicide prevention priests, who have developed their own regional training programs. In 2017, accessing the JNEB and INEB networks, the 1st International Conference on Buddhism, Suicide Prevention, and Psycho-Spiritual Counseling was held in Japan hosted by IBEC at its host temple the Kodo Kyodan Buddhist Fellowship 孝道山 (shown above). This conference has led to further such meetings, held twice in Thailand in 2019 & 2023, and the establishment of smaller conferences and training workshops. As indicated in the title of the first conference, the themes have gone beyond suicide prevention to include chaplaincy training for Buddhist monastics and professional skills training in intergrated Buddhist-based psychotherapy.

Tuesday, July 15, 2025

About Us

The INEB Institute for Buddhist Chaplaincy (IBCC) is a cooperative, network organization that supports Buddhist chaplaincy training programs in Southeast and South Asia

© 2025 IBCC