Re-Awakening to Our Inter-connected World

1st International Conference on

Buddhism, Suicide Prevention, and Psycho-Spiritual Counseling

Presentations from Japan

Contents:

- The Actual Situation and Countermeasures to Suicide: An Introduction to Japan and the City of Kawasaki – Dr. Tadashi Takeshima

- The Activities of Public Health Nurses and Countermeasures to Suicide – Ms. Takako Tsuda

- Suicide from the Viewpoint of Clinical Interviews and the Present Situation in Kyoto – Ms. Kyoko Murasawa

- Changes in the View of Suicide in Japan through the Terms “Self-death” (ji-shi) and “Suicide” (ji-satsu) – Rev. Sei Noro

- Problematic Issues in Buddhist Teachings and Institutions towards the Suicidal and their Families – Ms. Yukiko Takami

- Encountering Death and Building Life-Affirming Relationships – Rev. Jotetsu Nemoto

- The Activities of the Association of Buddhist Priests Confronting Self-death and Suicide of Tokyo/Kanto – Rev. Yukan Ogawa

- The Role of Traditional Buddhist Denominations in Facing the Suicide Problem from the Viewpoint of the Soto Zen Denomination – Rev. Zenchi Uno

- The Structural and Cultural Causes of Suicide and Community Breakdown in Rural Japan – Rev. Shunei Hakamata

- A Pure Land Buddhist Approach to Suicide Prevention and Training Priests in Interpersonal Encounter – Rev. Ryogo Takemoto

- The Activities of the Kansai Association of Buddhist Priests Confronting Suicide – Rev. Kazuhiro Sekimoto

- A Buddhist Approach to Telephone Counseling for Children – Rev. Hitoshi Jin

Go to Presentations from Other Countries

Dr. Tadashi Takeshima

Dr. Tadashi Takeshima

was born in Kochi prefecture in 1945 and graduated from Jichi Medical University in Tochigi. After working in the Public and Mental Health Center of Kochi prefecture, he became Chief of the Department of Mental Health Policy and Evaluation for the National Institute of Mental Health at the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry in Tokyo in 1997. Since 2006, he has been in charge of various offices at the Suicide Prevention Center of the same research institute. In 2017, he became Director of the Kawasaki City Health and Social Welfare Bureau and the Disabled People Welfare and Public Health Department. In 2018, he began working as Director General of the Mental Health and Welfare Centre.

In his talk entitled The Actual Situation and Countermeasures to Suicide: An Introduction to Japan and the City of Kawasaki, he pointed out the common misperceptions about suicide from the WHO report on suicide countermeasures; such as, “People who talk about committing suicide are really not considering doing it.”; “Only those people with mental disorders are prone to suicide.”; “It is not good to talk about suicide.” There is a need for great care in making judgements about those who have died committing suicide. It is easy to pass judgement, especially cases of those who have left behind wills after hanging themselves. There are also those who have had a mental illness and died after overdosing on medication being considered suicide. In this case, it’s not clear whether it is suicide or not, so a thorough investigation is needed.

In 2006, the Japanese government created an official policy towards suicide, and now in 2018, some 20 years later, they are seeing some positive results. A specific central aspect of this policy is support for bereaved families. Before and after this policy was developed in 2006, there was a great increase in the number of organizations nationwide dealing with this issue. From their work, he suggests a few policies to confront the current situation: 1) health issues as well as economic and livelihood issues are the main causes and factors for suicides, so measures targeting these issues should be promoted regularly; 2) since the suicide rate is high in municipalities with a high ratio of elderly people, the implementation of comprehensive activities focused on health care and long-term care for the elderly is important; 3) comprehensive analyses, like the ones they have conducted, will contribute to the implementation of measures based on the actual situation of target age groups and regions. Dr. Takeshima concluded by stating that he believes suicide prevention is about taking on “the restoration of the essential freedom of the individual” and “ending the misconception that suicide is a disgraceful form of death”. Suicide should not be seen as something that “weak” people do. It is possible that anyone could be forced into a situation in which they commit suicide.

Ms. Takako Tsuda

is the Manager of the Kawasaki City Mental Health and Welfare Center. She became a city employee of Sakai, Osaka Prefecture in 1988 but has worked as a city employee in Kawasaki, Kanagawa prefecture since 1992. As a public health nurse, she is active with the Mental Health and Welfare Center, the Children’s Support Office, and other institutions. She has also been organizing gatherings for bereaved families of suicidal persons as part of her current job since 2012.

is the Manager of the Kawasaki City Mental Health and Welfare Center. She became a city employee of Sakai, Osaka Prefecture in 1988 but has worked as a city employee in Kawasaki, Kanagawa prefecture since 1992. As a public health nurse, she is active with the Mental Health and Welfare Center, the Children’s Support Office, and other institutions. She has also been organizing gatherings for bereaved families of suicidal persons as part of her current job since 2012.

In her talk entitled The Activities of Public Health Nurses and Countermeasures to Suicide, she explained that in Kawasaki City, they have put effort into a comprehensive local care system that links, cooperates, and assists. It has been important to develop proper balance in self-care, mutual care and assistance, and public assistance. Before instituting this comprehensive local care system, staff were divided according to specific target groups. Based on this organizational restructuring, there is now a system of local staff who are able to handle a variety of specific aspects in a locality and engage in necessary activities. She noted that public health nurses need to think about how to implement suicide countermeasures. The first step is “prevention”, which involves activities to raise awareness about suicide and self-death among citizens. Another very basic form of prevention is installing barriers on the local train tracks to keep people from falling or jumping onto the tracks. The second step is “intervention”, which involves making a system of short term support and counseling. The third step is “postvention”, which involves support for bereaved families. Ms. Tsuda noted that she believes it is their role to communicate to the government these kinds of proposals that develop the social environment. Public health nurses can have an influence on individuals and families by using their fundamental skills and knowledge as medical professionals. Community building is one role they can take in their work as well as promoting the creation of social bonds through prevention activities and promoting the preservation of the health of individuals and local citizens. With the protection of life and the respect for life as a basic stance, they can engage in suicide prevention as one type of aid.

Ms. Kyoko Murasawa

is a specialist in psychology at the Kyoto Comprehensive Center for Mental Health and Welfare, where everyday at the center she conducts interview consultations. In her talk entitled Suicide from the Viewpoint of Clinical Interviews and the Present Situation in Kyoto, she explained that in the last year, suicide in Kyoto was the lowest it has been in the last 20 years and the fifth lowest in the nation. Compared to its highest level, it is now 40% lower. However, the rate among young people has not declined, and this is a similar tendency found all over the country. Suicide among men in their 20s is high, and it is common among university students. There are different causes for young people in their 20s and those in their teens. Amongst the former, clinical depression connected with work and salary is common; and amongst the latter, stress from study and trying to get into university as well as isolation and weak human bonds are common. Japanese society does not think it is good to quit your job before you die or that it is good to take a break from school. One does not receive sympathy from their family or people near them. We see this reflected in popular culture, such as in one manga that says, “The reason was the inability to quit work before they died.” Furthermore, the support systems nearby are also weak. The message that is communicated is of course that parents are concerned and worry about their children. However, there is the strong sense of undue pressure being put on the child and that they should not being a burden or trouble for others. She explained that methods like affirmation can have positive results. The individual needs to hear healing words like, “I accept you as you are. I recognize you. I love you.” Just through these things, a person’s feelings can calm down. In Asia, especially, Japan it is quite common for psychological stress to be expressed in the body. In Japan, there is an unusually strong prejudice against mental illness, so it takes a long time to notice the onset of it is because people do not want to speak out about their experiences. As such, the percentage of students in junior high school and at college preparation schools who visit the specialist at the health office is about 10%.

a specialist in psychology at the Kyoto Comprehensive Center for Mental Health and Welfare, where everyday at the center she conducts interview consultations. In her talk entitled Suicide from the Viewpoint of Clinical Interviews and the Present Situation in Kyoto, she explained that in the last year, suicide in Kyoto was the lowest it has been in the last 20 years and the fifth lowest in the nation. Compared to its highest level, it is now 40% lower. However, the rate among young people has not declined, and this is a similar tendency found all over the country. Suicide among men in their 20s is high, and it is common among university students. There are different causes for young people in their 20s and those in their teens. Amongst the former, clinical depression connected with work and salary is common; and amongst the latter, stress from study and trying to get into university as well as isolation and weak human bonds are common. Japanese society does not think it is good to quit your job before you die or that it is good to take a break from school. One does not receive sympathy from their family or people near them. We see this reflected in popular culture, such as in one manga that says, “The reason was the inability to quit work before they died.” Furthermore, the support systems nearby are also weak. The message that is communicated is of course that parents are concerned and worry about their children. However, there is the strong sense of undue pressure being put on the child and that they should not being a burden or trouble for others. She explained that methods like affirmation can have positive results. The individual needs to hear healing words like, “I accept you as you are. I recognize you. I love you.” Just through these things, a person’s feelings can calm down. In Asia, especially, Japan it is quite common for psychological stress to be expressed in the body. In Japan, there is an unusually strong prejudice against mental illness, so it takes a long time to notice the onset of it is because people do not want to speak out about their experiences. As such, the percentage of students in junior high school and at college preparation schools who visit the specialist at the health office is about 10%.

People often have anxiety and reactions to anniversary dates of past events. At this time, thoughts about the past arise as well as past traumas. From religious teachings, one can expect to gain relief from the anxiety of facing death and the feeling of personal responsibility for the deaths of loved ones. Compared to the past, the generation gap is wider now. The way of thinking and communicating about everything is strongly influenced by one’s mother. Children often have a feeling of personal responsibility when a parent dies. Since they have a self-centered value system of either being good or bad, they easily turn responsibility towards themselves. No matter what you say to them, it cannot completely wipe away this feeling, so Murasawa uses a technique for externalized their frame of thought by saying, “From the perspective of your parents, what would you think?” Ultimately, she thinks it is most important to have someone nearby who is stable and is respected.

One counter measure the Kyoto government has taken is a free suicide prevention center using the app LINE. There are also courses being offered to university students for credit on preventing suicide. Finally, there is an annual event for suicide prevention held as a public-private partnership, which is uncommon in most of Japan. Murasawa is also putting efforts into building a class in mental care for home delivery, especially for primary, junior high, and high school kids. There are also courses that have increased the desire for support, such as prevention and resiliency programs like the Penn Resilience Program (PRP) used in schools and the Master Resilience Training (MRT) programs used by the military in the United States. It is felt that it requires at least ten years from developing a dangerous problem to seeking out counseling, so their target is from 4th graders in primary school to younger. Reducing the pathology of depression and increasing self-actualization are positive effects. While using a program in cognitive behavior therapy which asks questions like, “What can you say in dealing with a close friend?”, they have also developed their own programs, which are enjoyable for students. These have a good effect on both students who attend and who don’t participate. The ones who attend and have fun naturally tell the others to come and join.

At present, the Kyoto government does not link with religious professionals. In counseling people who are in a difficult situation, Murasawa reported that they first get them in touch with emergency forms of support for issues like finances, employment, and human relationships. However, she feels there is a need for a shift in the fundamental value system of society and that once someone can be stabilized, it is possible to link with a religious professional.

Rev. Sei Noro

is a Research Fellow at the Ryukoku University Research Center for Buddhist Cultures in Asia (BARC) in Kyoto. In his talk entitled Changes in the View of Suicide in Japan through the Terms “Self-death” (ji-shi) and “Suicide” (ji-satsu), he explained that in the earliest Japanese historical documents like the Kojiki from the 8th century, the term ji-shi (translated as “self-death”) occurs, while the term that is standard today ji-satsu (translated as “self-killing”) does not appear. Moving into the 10th century, the term ji-satsu begins to appear but is not used in a clearly pejorative way. By the Edo period (1603-1868), ji-satsu appears in numerous poems and novels related to unfulfilled romance, such as a woman or two lovers together committing suicide.

is a Research Fellow at the Ryukoku University Research Center for Buddhist Cultures in Asia (BARC) in Kyoto. In his talk entitled Changes in the View of Suicide in Japan through the Terms “Self-death” (ji-shi) and “Suicide” (ji-satsu), he explained that in the earliest Japanese historical documents like the Kojiki from the 8th century, the term ji-shi (translated as “self-death”) occurs, while the term that is standard today ji-satsu (translated as “self-killing”) does not appear. Moving into the 10th century, the term ji-satsu begins to appear but is not used in a clearly pejorative way. By the Edo period (1603-1868), ji-satsu appears in numerous poems and novels related to unfulfilled romance, such as a woman or two lovers together committing suicide.

It is not until the Meiji period (1868-1912) that the term ji-shi disappears. For example, in the well-known national newspaper the Asahi Shimbun which was founded in 1879, we can find tens of thousands of articles using ji-satsu but only a handful using ji-shi. The increase in usage of ji-satsu in the Edo period made it part of common speech entering the Meiji. However, the more central reason for the shift into ji-satsu as a pejorative term comes from the translation of a wide range of western books that began with the opening of Japan in the Meiji period. For example, an 1874 translation of British legal documents shows the criminalization of suicide based on the taking of one’s life which has been given by God. Because of the negative view of Christianity towards suicide and its influence on western literature and law, the term ji-satsu was seen to be a more appropriate translation. Further, by turn of the 20th century, Christians began to criticize Buddhism as a religion of pessimism because of its negative view of the world as a place of suffering and the longing to be reborn in the Pure Land of Amitabha. Valid or not, this was seen as a reason that the Japanese did not view suicide as negative. Thus, under siege from the new pro-Shinto Meiji government and the increasing influence of the Christian West, Japanese Buddhists defensively reacted and began to write more openly about how Buddhism also condemns suicide.

Since 1966, ji-shi has come into use again, especially as seen in the current names and work of the new Buddhist suicide and self-death prevention organizations. While Rev. Noro thinks it is good to revive the non-pejorative term ji-shi, he feels it is also not good to just entirely stop using ji-satsu. As there are a wide variety of contexts, a diversity of language to reflect these nuances is important to maintain. In the discussion period after his talk, a participant noted that in the United States new terms are being developed like, “death with dignity”, when the sick and elderly commit a form of assisted suicide or termination of life, and “compassionate extubation”, when taking someone off life support. In Korea, there are two different terms to distinguish between those who violently commit suicide and those like the elderly who choose “death with dignity”. In Germany, there are two terms that translate as “self-killing” and “suicide”, the latter being used in more formal speech. Interestingly, like Japan, there is another old term used in classics like those of Goethe that can be translated “free-death”. This term, however, is not used in everyday language.

Ms. Yukiko Takami

is from Remember: The Nagoya Association of Bereaved Families from Self-death. Today in Japan, many people, especially the survivors of suicide, have a problematic relationship with Buddhism, its institutions, and its priests. A major problem are the traditional Japanese Buddhist funeral customs. Suicide usually comes suddenly, and the family is totally unprepared to deal with it and the costly set of Buddhist based funeral customs. On the day of the funeral, families have to make a cash offering—called ofuse 布施, or dana in Sanskrit/Pali—to the priests for their services. Amidst the shock and anguish of the sudden death, the family also has to suddenly gather a large sum of money. The increase in stress at this critical moment of grieving can severely damage any sense of trust or any feeling of compassion being offered by such priests. Many people have no belief in religion nowadays, so no matter how wonderful the service might be, they rarely understand its significance and it having any serious financial value.

Japanese have come to see Buddhism as a religion that discriminates against people based on how they die, especially those who commit suicide. There are various popular phrases that express the belief that any bad experience or unfortunate death is the deserved result of karma; i.e. “you reap what you sow”. There are even cases of people who show up at funerals and mutter these things out loud during the service. She feels that these words are not being used in the original, proper meaning. Buddhist denominations should better explain these deeper meanings to overcome these damaging behaviors, which are also damaging Buddhism’s public image.

Twelve years ago, Remember conducted a survey in which many people mentioned experiences of Buddhist priests hurting them with insensitive comments about their deceased loved one. They decided then to hold a special seminar to support suicide survivors on how Buddhism could better address the suicide issue. The seminar attempted to clarify Buddhist teachings. For example, the first precept of Buddhism, “to not kill”, does not refer to people who take their own lives. Further, there are important examples like the Buddha’s disciple Channa, who in the midst of a terrible, debilitating illness took his own life by knife. When two other disciples, Cunda and Shariputra, who had been attending to Channa, asked the Buddha about Channa’s fate, he responded that since Channa had already attained enlightenment and was an arhant, his act was blameless and not unskillful. In Nagoya, there is a group called the Association of Religious Professionals Confronting Life established in 2011, which has been holding special memorial services (tsuito hoyo) and group counseling sessions (wakachi-ai) for the bereaved families of suicide. Thanks to the efforts of this group, the relationship between religious professionals and common people on these issues is being improved and rebuilt. In May of 2017, Remember took another survey that showed a mostly positive experience with priests on these matters of suicide and death.

Rev. Jotetsu Nemoto

Rev. Jotetsu Nemoto

presently serves as the Chief Priest of Daizen-ji, a Rinzai Zen temple in Seki City in Gifu Prefecture. In his presentation on Encountering Death and Building Life-Affirming Relationships, he spoke of his experience with suicide in his youth that led him in 2004 into engagement with the suicide issue through the internet, developing chat groups and a personalized style of internet counseling and chaplaincy. By 2009, after answering thousands upon thousands of e-mails and telephone calls at all hours of the day and night, his attempt to apply his rigorous Zen training to suicide prevention work gave way to a serious heart condition at only the age of 37 and an extended stay in the hospital. This experience led him to cut back on e-mails and cell phone use and to require that those who wanted his counsel to come visit his temple, even though its location is quite remote. This new approach led to positive results for both the people who visited and for himself. After such face-to-face encounters, he often felt that some kind of resolution has been achieved. The achievement of a resolution and the intense interest in the mechanism that leads one either to life negation or life affirmation is a special focus of Rev. Nemoto’s chaplaincy.

In 2010, Rev. Nemoto broadened his work by creating Ittetsu Net, a network for building friendships and holding workshops for mental and physical health, emphasizing self-care and outdoor activities. He is also a representative for the Association of Religious Professionals Confronting Life, a suicide prevention group based in Nagoya that is similar to other such regional associations. From his temple, Rev. Nemoto has continued to develop group gatherings confronting the issue of life and death from very Buddhist foundations. In the past, Rev. Nemoto had organized events with suicidal people from his chat groups, such as casual get togethers for meals or more organized outings to famous places for committing suicide to learn from and pray for those who had passed before. However, moving on from Internet chaplaincy and developing more face-to-face work, Rev. Nemoto has started to hold events for all sorts of people, not just the explicitly suicidal. For interested people in his wide network and also for specific groups of businessmen and office workers, he has developed death workshops at his temple.

In this death workshop called The Departure (tabidashi), participants imagine they have been given a diagnosis of cancer and have three months to live. He instructs them to write down the ten most important things in their lives, such as possessions, friends, family, even ideas or values. Then, after telling them they have terminal cancer, he instructs them to choose which things they must give up or abandon until they are down to their final thing at the moment of death, which they must also let go off. Participants then act out their existence after death by going into the main Buddha hall, lying down, and putting a white cloth over their face, while Rev. Nemoto conducts a funeral ceremony. Then, they carry lit candles up a hill behind the temple to imagine entering the world of the dead. These exercises create a wide range of emotions from deep sadness in the experience of dying to even exhilaration in the post-mortem experience.

In this way, Rev. Nemoto is working on getting deeper at the roots of the suicide problem in Japan by shifting his focus on helping specifically suicidal people one-on-one to working with groups of people sharing a wider range of anxieties and then working to build back communities of connection based around healthy living. Through his years of work, he has found the prevalent model of volunteers and counselors working in a one-way relationship with the mentally ill and disturbed just does not work. Eventually, the former get tired and burned out, and the latter just get tired of them and their flagging commitment, in a downward spiraling pattern. Rev. Nemoto seeks to build a more dynamic framework of interaction in which a variety of different groups are united in the central ideal of “self-care”. In these activities, people enjoy themselves in a more playful manner, which then draws in an even greater diversity of people. Within this dynamic container, Rev. Nemoto recounts, counseling takes place naturally at these events.

Rev. Nemoto also works as a representative for the Association of Religious Professionals Confronting Life which has activities in the city of Nagoya. Five times a year they hold discussion groups for bereaved families. This work is not just by religious professionals as they also link with groups that support bereaved families. They also do not do this work just for self-satisfaction but have the basic view that receiving critical feedback is important. Once a year, they hold a special memorial service, where they get questions like, “When I die, will I be able to meet my dear relative who committed suicide?”. In responding to such questions, he reports that it is most important that the person gets the feeling that the priest/counselor is seriously concerned about them.

Rev. Yukan Ogawa

Rev. Yukan Ogawa

presently serves as the Chief Priest of Renpo-ji Temple of the Jodo Pure Land Denomination, located in Fuchi City in western Tokyo. He works as a Senior Researcher at the Center for the Promotion of Buddhist Social Responsibility (BSR) of the Taisho University Area Studies Institute in Tokyo. Since 2008, he has participated in the Association of Buddhist Priests Confronting Self-death and Suicide of Tokyo/Kanto, working to support bereaved families of those who have committed suicide. He is also involved in children’s grief care as board member of Egg Tree House.

In his talk entitled The Activities of the Association of Buddhist Priests Confronting Self-death and Suicide of Tokyo/Kanto, Rev. Ogawa explained their core activities of letter counseling in which they exchange letters with people facing suicide, special memorial services for those who have committed suicide entitled “A Day of Life, A Time for Life”, and group counseling sessions for bereaved family members. Formed in 2007, this association was the first group to develop these activities, which have now become common to a variety of Buddhist groups concerned with the issue.

The idea behind counseling by letter is to ascertain the background details of the person. In such a situation, Rev. Ogawa noted that it is important to focus on the emotional tenor rather than asking questions. By writing a letter, the person may find it helpful through adjusting or rearranging the issues and slowly working through a complicated matter. With the letter always available for reference for the client, they hope to provide a sense of warmth for them at anytime. Furthermore, by using traditional Japanese brush pens, a certain emotional subtlety and state of mind can be expressed between the priest and client which may be helpful. The goal is to support them to regain their footing by their own power.

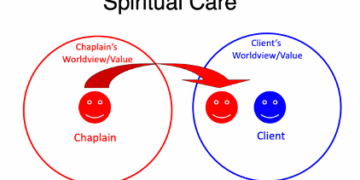

Rev. Ogawa also explained that it is important in the work of religious professionals to prevent suicide to not take the stance of trying to treat or cure people, but rather to accept them as they are. The priest needs to serve as a refuge and to provide a place where people can escape the common values of society. Bereaved families are often unable to speak about the suicide of an important family member, so they suffer in a special kind of silence. Society has many prejudices against the suicidal, so it is important for bereaved members to gather together and share their feelings. They conduct such gatherings once every month with an average of 40 people in attendance, much more than the number of other such groups holding such sessions.

The group also holds special memorial services once a year for around 150 participants. Due to various reasons, many families do not gain any satisfaction from the funeral of their suicidal loved one. Families may also have become divided with other relatives criticizing the main family. There are few opportunities to provide any care as the funeral becomes a place of suffering. From the written reflections received at the end of this event, they have been able to understand how families have made a connection with the departed loved one, for example, “I was able to express my thoughts to my father.”; “Although it was brief, I felt I could meet with my daughter again.” By offering a place to mourn, people can make a connection with the deceased and recall them in ease without the discrimination attached to suicide.

Rev. Zenchi Uno

Rev. Zenchi Uno

is a Research Fellow at the Soto Zen Denomination Research Center in Tokyo. After graduating in Biology from the Faculty of Science at Yamagata University, he began working as a research staff member of the Soto Zen Institute for the Cultivation of Soto Teachers at the headquarters temple of Eihei-ji in Fukui. He is involved in the planning and management of workshops to train Soto Zen priests in counseling and in the conducting of memorial services by the Soto sect headquarters for the bereaved families of suicides.

In his talk entitled, The Role of Traditional Buddhist Denominations in Facing the Suicide Problem from the Viewpoint of the Soto Zen Denomination, he explained that the traditional Buddhist denominations of Japan do not seriously confront people who are dealing with anxiety and depression. As such, there is an urgent need for the traditional denominations to renew a process of critical self-examination and rediscover the core meaning of the Buddhist priest and temple. One important activity in such a process would be for temples to engage in counseling for those in suffering. Rev. Uno noted that in the way one has a regular family doctor, one should have a regular family temple, where one can come to first with any kind of anxiety or insecurity to speak with the abbot or his wife/their partner who offer “presence” and “deep listening”. However, this is not so simple. The words that one thinks are right for someone to hear may actually hurt them. A Buddhist priest has much pride in their ability to sermonize, yet their weakness is in listening to what others have to say.

The Soto Zen denomination has created a study and training curriculum for the purpose of “facing life” for their roughly 11,000 priests training in 50 centers around the country. The focus is not just on academic study for giving dharma talks but also providing experiential training, which includes consultation through letter writing. They are providing an experience for how priests can respond to others in suffering by providing the contents of actual cases. Bereaved families are also at high risk of suicide, so for supporting such families they have created special memorial events twice a year with participants joining from all over the country. At these events, family members have spoken of the harmful comments made by some priests about their suicidal family member and how those words made them depressed. Further, there have been cases of people who have died by suicide being given discriminatory posthumous dharma names. The problem of priests being prejudiced against the suicidal is a serious issue. At their special memorial events, officially sanctioned priests provide a proper funeral service for those who have committed suicide, and the Soto sect is able to fully actualize the important role of supporting the bereaved.

A third important role that priests can take on is what is called here in Japan a “gatekeeper”, that is a person who offers a window or entry point for the support of people with depression and anxiety. Because a priest is there for the traditional memorial services that take place soon after the death, they are often able to properly ascertain a family’s makeup and situation. On the other hand, workers at public health facilities often say that, “We know that there is a high risk of suicide among bereaved family members, but they have a hard time coming to us about it.” In this way, there is great potential for the priest to take on the role of a “gatekeeper”. In conclusion, Rev. Uno expressed his hope to connect the ideal of the Buddhist practitioner to heal suffering and offer peace with this restoration of the family situation. In order to be a true Buddhist priest and also in order to realize the function of the temple, he thus feels that it is important that priests get involved in the problem of suicide.

Rev. Shunei Hakamata

Rev. Shunei Hakamata

is the Chief Priest of Gessho-ji, a Soto Zen temple in Fujisato-cho, Akita prefecture in northernmost Japan. In 2000, he founded the Association for Thinking about Mind and Life, a suicide prevention group. In 2010, he became the Chairman of the Board of the Akita Prefecture Flower Bud Movement, which was the first prefectural level suicide prevention movement in Japan. He also serves on the Tohoku regional board of directors of the Japan Association of Euthanasia, as the Vice President of the non-profit suicide prevention network Kaze (wind), and as a part time lecturer at the Japan Red Cross’ Akita Nursing University.

In his talk on the Structural and Cultural Causes of Suicide and Community Breakdown in Rural Japan, he explained that Akita prefecture has a high rate of suicide and for many years had the highest rate on record in the nation. One important reason for the high suicide rate is the stagnation of the local economy, which has happened in many remote, rural areas in Japan. Rev. Hakamata has delved deeper into the structure and culture of suicide in his region, and he has found that one of the issues related to suicide in the area is the phenomenon of the types of communities that develop near mountainsides. They have been found to exhibit the peculiar characteristics of a weak sense for the desire to receive help and avoidance to be a bother to their neighbors. Living in mountainous areas, one must learn to be strong and self-sufficient, yet at the same time one cannot live without the support of others. Here, one has to be able to offer something in order to receive something; it’s a sense of reciprocity and mutual aid.

Rev. Hakamata noted that he used to think until recently that the problem was related to weak human bonds but in reality the problem is the quality of the bonds. In the areas that have strong human bonds but also suffer from depopulation, the values of not bothering others, not taking someone away from their work, and not sending out an S.O.S. are strong. Thus the rate of suicide is still high. For example, the suicide rate of elderly who live together with families in three-generation households is actually higher than those who live alone. It is common for them to feel as they get old that they have lost their role in the house, should not be a bother, and are in debt for their existence. In the past, the elderly took on the important role of running local festivals. In farming households, the grandparents would look after the grandchildren and take the role of looking after things. However, the emergence of social systems like child care changed this, and their roles ended as one could get government services for even the afterlife. He concluded that there is a need then for a change in the quality of bonds. Basically, it is not necessarily good when the number of bonds or connections increases. Rather, things need to be a little looser, and there is a need to shift from the sense of “monitoring” the elderly as a service provider to a sense of “having concern for” the elderly as a member of the community.

In response to this situation, Rev. Hakamata established the Association for Thinking about Mind and Life and opened a café called Yottetamore in 2000. He noted that there is a strong tendency to have troubles with life and to get oppressed by the surroundings in his region. The people in his area who are seen as eccentric or difficult to deal with gather as regular customers at the Yottetamore café. The role of Buddhism is to serve the function of offering a refuge to escape society and also embody a different value system. Looking at things from the viewpoint of economy being the top priority, people who are unproductive are seen by society as a nuisance that has to be “dealt with”. However, looking at it from a Buddhist value standpoint, no one should ever be “dealt with”. They have expanded this activity, and now there are such cafes in many cities, towns, and villages in Akita. Although they have been doing these activities for many years, he noted that it is unfortunately difficult to see any definitive results in suicide prevention.

In Akita prefecture, there are about 200 Soto Zen temples. The regional “gatekeeper” instructional course is required for all priests. There are many cases in which a priest listens to the words of a person in suffering and feels they must deal with the situation by saving them by themselves. When there is a strong sense of duty to save others by oneself, the priest feels they must handle everything, but in this case it is important to seek out various other specialists. According to the suffering person’s specific type of anxiety, a priest should connect them to the proper specialist. It is important that the priest has a clear understanding of what they can and cannot do. There are many cases of someone with deep suffering receiving counseling and either being very grateful or refusing it. Through learning how to become a “gatekeeper”, a priest can reduce the situations they can’t handle by making connections with a wide network of specialists. see more details here

Rev. Ryogo Takemoto

is a representative of the SOTTO Kyoto Self-Death & Suicide Counseling Center and a former member of the Hongan-ji Jodo Shin Sect Research Institute. In his presentation on A Pure Land Buddhist Approach to Suicide Prevention and Training Priests in Interpersonal Encounter, Rev. Takemoto spoke of his own discovery of how specific teachings within Buddhism helped him understand and help support those who wish to die. He has tried to tie together the concept and the activity of spiritual liberation for ongoing counseling work.

is a representative of the SOTTO Kyoto Self-Death & Suicide Counseling Center and a former member of the Hongan-ji Jodo Shin Sect Research Institute. In his presentation on A Pure Land Buddhist Approach to Suicide Prevention and Training Priests in Interpersonal Encounter, Rev. Takemoto spoke of his own discovery of how specific teachings within Buddhism helped him understand and help support those who wish to die. He has tried to tie together the concept and the activity of spiritual liberation for ongoing counseling work.

He explained that it has become popular to say that, “The person who holds the idea of wanting to die actually wants to live.” However, Buddhism sees this in a different way. It is not about a fixed idea of “I want to die”, but rather from the influence of a small, seemingly insignificant event that creates a kind of feeling and then in turn a specific action. For humans, a small insignificant feeling can cause change in us. Further, from the Buddhist viewpoint of dependent origination, self and other are tied together. One receives influence from what is around them, and in turn influences things around them.

In terms of liberation, Buddhism teaches a variety of paths. Concerning two methods of easing suffering, there is the one path taught by Shakyamuni Buddha of liberation through one’s own practice and another of liberation through Amida Buddha’s guidance. The former is the path of self-control through practice and the latter the path of encounter with another. However, the spiritual liberation gained through an encounter with Amida and the liberation through encounter with another person are clearly different. As our existence is one of fundamental solitude or loneliness, the experience of liberation through an encounter with Amida Buddha can bring light to this basic isolation. It is an experience with an encounter with light. One does not find a resolution to every single matter through Amida Buddha, but through this encounter with light, our way of perceiving our surroundings can change. Since I myself have not attained enlightenment, I cannot liberate anyone by my own will. However, I can communicate warmth to someone who is suffering before me. Interpersonal support cannot bring light to one’s fundamental darkness, but it can communicate warmth to a person that is before oneself. In western thought, humans consist of body and mind, but in Buddhist thought, life is defined by breath and heat. For those people who need support, an interpersonal encounter can help lighten their feeling of isolation by transmitting warmth to them.

At SOTTO, they do not use any Buddhist terminology at all, because although some people who seek their counseling are Buddhist, others are not. Further, there are so many different schools of Buddhism, it is hard to speak to each person according to their own specific school of thought. From both their experience working with people and from the standpoint of their faith as Pure Land Buddhists, they find that the individual’s personal religious view is beside the point. They have found interpersonal encounter to be a more effective way of supporting people rather than trying to instill in them a specific form of religious practice, which might be different from theirs or basically non-existent as a non-religious person.

Rev. Koyu Tsurono and Rev. Chikai Abe then led a special session to introduce the training methods of the SOTTO Kyoto Suicide and Self-death Consultation Center and provide an example of one of their role-plays for counseling groups. They explained that the topic of suicide can appear often in counseling in Japan when someone says “I want to die”. As such feelings cut across many demographics in Japan, a variety of types of professionals may encounter people with such feelings, such as social workers, psychiatrists, religious professionals, health professionals, etc. There is also the need to support bereaved families. When they began SOTTO in 2010, they had 10 volunteer counselors, which has now increased to 70 volunteer counselors from Buddhist, Christian, and Shinto organizations.

The main part of the curriculum is the role-play training. Besides the person who acts as a client and the person training as a counselor, there is the role of a facilitator and an observer. The facilitator makes sure everything goes smoothly in the practice session, and the observer evaluates the whole session, especially the counselor. Often, there will be more than one observer, and the facilitator will also share feedback. Adequate time is taken at the beginning for preparation and also for reflection at the end. The counselor will also be able to ask the observers and other people for feedback and to answer questions.

Once a month, they take time to share reflections amongst the working volunteer staff and spend time with consultant leaders in the movement to help them self-reflect on certain cases they have handled. They also have a session for all the counselors to gather and talk about cases they have had, especially cases in which they have taken in negativity. Concerning self-care, Rev. Tsuruno expressed that he can get depressed from the work. In the early days, he thought he had to save people and that created a much heavier impact on him. As a priest, he would go into the main hall at Nishi Hongan-ji temple to pray and be quiet in front of the Buddha image. Now he has learned about what he can and cannot do, so is able to draw the line better and not take on all the suffering of the client.

Rev. Kazuhiro Sekimoto

is the abbot of Dainen-ji Temple of the Yuzu Nenbutsu Sect, former board member of the International Befrienders Osaka Suicide Prevention Center, and former representative of the Kansai Association of Buddhist Priests Confronting Suicide. In his presentation on the Activities of the Kansai Association of Buddhist Priests Confronting Suicide, he explained how the Kansai Association was created by priests who felt they needed to do something before people die as opposed to the usual role of priests being only involved after death. In their association, they have engaged in the following activities: 1) end of the year special memorial service (tsuito hoyo) for only bereaved families. Since families are often so busy with all the work of the funeral procedures, like the wake and cremation, they do not really have proper time to grieve. At this special service, there is the time to properly re-grieve; 2) a counseling session for bereaved families called the Gathering of Life. Held on the first Monday of odd months, family members are divided into groups of 3-4 persons with a Buddhist priest facilitator, usually totaling 5 groups. At this time, they refrain from making comparisons, allow for periods of silence, and do no repeat the stories to outsiders. The priest facilitator basically does not talk but acts more to “direct the traffic” of the interaction. This is the typical format of other such associations around the country; 3) a bereaved families group only for men. Held on the first Friday of even months, the groups focuses on men since they tend to have a particularly difficult time expressing grief and crying in front of others as well as talking about their weaknesses and expressing their emotions; and 4) counseling by written letter.

is the abbot of Dainen-ji Temple of the Yuzu Nenbutsu Sect, former board member of the International Befrienders Osaka Suicide Prevention Center, and former representative of the Kansai Association of Buddhist Priests Confronting Suicide. In his presentation on the Activities of the Kansai Association of Buddhist Priests Confronting Suicide, he explained how the Kansai Association was created by priests who felt they needed to do something before people die as opposed to the usual role of priests being only involved after death. In their association, they have engaged in the following activities: 1) end of the year special memorial service (tsuito hoyo) for only bereaved families. Since families are often so busy with all the work of the funeral procedures, like the wake and cremation, they do not really have proper time to grieve. At this special service, there is the time to properly re-grieve; 2) a counseling session for bereaved families called the Gathering of Life. Held on the first Monday of odd months, family members are divided into groups of 3-4 persons with a Buddhist priest facilitator, usually totaling 5 groups. At this time, they refrain from making comparisons, allow for periods of silence, and do no repeat the stories to outsiders. The priest facilitator basically does not talk but acts more to “direct the traffic” of the interaction. This is the typical format of other such associations around the country; 3) a bereaved families group only for men. Held on the first Friday of even months, the groups focuses on men since they tend to have a particularly difficult time expressing grief and crying in front of others as well as talking about their weaknesses and expressing their emotions; and 4) counseling by written letter.

In explaining the detailed work of counseling by priests, Rev. Sekimoto first explained about the practice of “deep listening” or keicho 傾聴 in Japanese. The second character, often pronounced as yuru 聴, is not the usual term used for “to listen” . It has a deeper sense of acceptance or allowing anyone in without judging or classifying. They have found in their work that by allowing someone the space to say “I want to die”, there is a therapeutic effect of release in being able to say something one hasn’t been able to say to anyone.

Rev. Sekimoto further spoke about the two ways to eliminate suffering. The first is “cure”, which are the treatments, measures, and solutions one takes to end the illness. The other is “care”, which is to intervene, to watch over, and to provide medical and psychological support services that may not actually result in cure. For example, someone who is involved in “cure” is focused on eliminating the disease like getting rid of cancer in the body. However, their approach in suicide prevention is more “care” in which they must accept the disease and work with it that way. For a bereaved family member, they cannot bring the dead back to life like it would be to “cure”, so they focus on “care”, which is coming to terms with the reality that the loved one is gone.

In referencing Buddhist teachings, Rev. Sekimoto spoke of the three forms of karmic action (body, speech, and mind) through which we can injure others. The Buddhist texts say these are interconnected. Thus, when the mind is overflowing with anxiety, it comes out in the body through things like insomnia, over eating, under eating, violent behavior, etc. One way he has found to deal with these situations is to use the mouth to expel the anxieties in the mind, like saying “I want to die”, as short term therapeutic remedies. Those who say they want to die the most usually do not do so. In this way, he does not try to block these voices in the mind but allow a space for their expression. Many people fear the judgements and consequences of sharing their inner feelings, so he feels we must alleviate this anxiety. Unfortunately, Buddhist priests who have been through much training have a strong sense of trying to save people, and they do not realize how they do not properly listen. The priest must understand what they can do and cannot do and make this clear to the suicidal and bereaved who in the end must take responsibility for their own lives. The temple should be a place where people can unleash their burdens, so ideally all priests should be able to practice deep listening and provide such support.

Rev. Hitoshi Jin

Rev. Hitoshi Jin

is Executive Director of the Zenseikyo Foundation & Buddhist Council for Youth and Child Welfare. He also serves as Senior Researcher at the Rinbutsuken Institute for Engaged Buddhism (under Zenseikyo), Representative Director of the NPO Childline Support Centre, and Supervisory Board Member of the International Institute for the Study of Religions. In addition, he is a Board Member of the Japanese Association for Mental Health, a part-time Lecturer at the Tokyo Jikei University School of Medicine, and Advisor of the Sarnath Dharma Chakra School and the Chief Priest of Sarnath Dharma Chakra Vihara in India. Since the 1980s, he has been working on the problems of young people in Japan like social withdrawal, school refusal, and suicide.

In his talk on A Buddhist Approach to Telephone Counseling for Children, he explained about Child Helpline International, which works in 145 countries around the world and engages in about 3,000 consulting cases per year through telephone and internet. As an international NGO, it principally takes on the suffering of children by listening to their voices. The organization began in the Netherlands in the 1970s and uses as its base the activities of the Samaritans organization in the U.K., where telephone counseling for abuse first began. Children often do not want to speak about their feelings with parents or teachers. While dealing with the suffering of children directly is important, it is also essential to confront socialization and social systems. In this way, one of their roles is to do fundraising and conduct training for other non-profits in the field.

In every country in Europe, there is not only Childline telephone consulting but also internet consulting. Last year in Japan such internet counseling began. The reality is that young people are using telephones less and are mostly using the internet through their smart phones. As the price for smart phones continues to decline, the number of young people using them and not using telephone lines is increasing so the Childline telephone counseling service cannot be accessed. In this way, he imagines an increasing need for counseling via the internet.

The activities of Childline have the basic stance of absolute respect, not relative, for the existence of life all over the world. There are three key points that come out of this philosophy: 1) to offer a place of safety and security for respecting children’s existence as humans, 2) to offer a place for children to cultivate awareness of their own power and the strength to live from the viewpoint of mindfulness, 3) to grapple with the socialization of children’s voices and thoughts from the standpoint of engaged Buddhism.

Using a Buddhist approach, they practice telephone and internet counseling. From the standpoint of Buddhist thought, children and all beings have buddha nature and developing this buddha nature is empowering. There are many cases of children having answers within themselves. They make telephone calls to confirm these solutions. They do not need to be taught anything. Children who have been bullied and harassed have very low levels of self-esteem. There are very few Japanese children in particular who feel themselves individually valued as human beings. In this way, they have put much effort into their suicide prevention program at Childline and have begun an outreach program with schools and children’s centers. Rev. Jin concluded by asking, is it possible to listen deeply to their stories, to more deeply introspect, and to change our awareness? Can we even speak about our own suffering, face it, or understand it?