two seminars on disaster trauma for caregivers in Myanmar by Japanese Buddhist chaplains

Introduction: Three Levels of Disaster Support

On March 28, 2025 at 12:50 p.m., a 7.7 magnitude earthquake followed by a 6.4 magnitude tremor struck the Sagaing Region of Myanmar with its epicenter close to the nation’s second-largest city Mandalay (population 1.7 million). Within two days, at least 2,928 bodies were recovered with thousands more injured. By the end of May, 5,352 fatalities had been reported with 11,404 people injured and hundreds more reported missing.

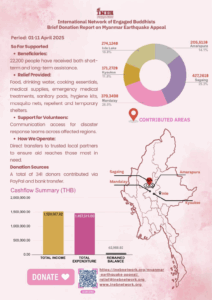

The International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB) immediately launched a humanitarian campaign for aid focusing on bringing food, clean water, blankets, medical supplies, emergency shelters, and other essential items to communities most in need. By the end of May, INEB had raised over $45,000. While this amount pales to the level of giant global aid organizations, the money is not wasted on large bureaucratic systems to deliver aid but rather has gone directly to INEB partners at the grassroots.

The International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB) immediately launched a humanitarian campaign for aid focusing on bringing food, clean water, blankets, medical supplies, emergency shelters, and other essential items to communities most in need. By the end of May, INEB had raised over $45,000. While this amount pales to the level of giant global aid organizations, the money is not wasted on large bureaucratic systems to deliver aid but rather has gone directly to INEB partners at the grassroots.

A second stage in the disaster is the shift from material aid to psycho-spiritual aid for those traumatized by the loss of loved ones and the unbearable destruction of their lives. On March 11, 2011, another great disaster similarly affected the people of Japan in what is called the Great Eastern Japan Disaster of earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear accident, which claimed 19,759 lives and forced 228,863 to evacuate. This latter number does not include another 164,000 persons who have permanently evacuated from the nuclear disaster area. Like INEB in Myanmar, many Buddhists in Japan at the time became active in material aid efforts. Many also became involved in grief care for the survivors by working tirelessly to make sure all those who had perished received proper burial rites and memorial services, the core of Japanese religiosity.

What we might call a third level of response took place amongst a small group of Buddhists who had already been working in the fields of Buddhist chaplaincy, end-of-life care, suicide prevention, and counseling. They began to train other Buddhists, both ordained and lay, in the deep work of confronting serious levels of trauma among not only survivors but also aid workers, who experienced numerous harrowing scenes during the disaster and for days and weeks afterwards. In the past 14 years, Interfaith Chaplaincy (rinsho shukyo) and Buddhist Chaplaincy (rinsho bukkyo) training programs have been established to help cultivate compassionate listeners that support people to discover their own paths of healing.

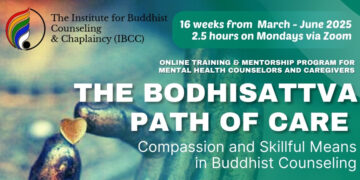

Through INEB’s Institute of Buddhist Counseling and Chaplaincy (IBCC), recently founded in January of this year, two leaders of these Japanese programs were contacted and requested to provide online seminars for a varied group of health care professionals (monks, nuns, psychiatrists, medical doctors, yoga teachers, etc) in the Mandalay and Sagaing regions. The group in Myanmar has been coordinated by Ven. Panna Theri of Shan State University, where she is building a Buddhist chaplaincy training program, and Anchalee Kurutach of the INEB office in Bangkok. In early March, just weeks before the earthquake, she participated in IBCC’s program in Thailand in suicide prevention with Rev. Jotetsu Nemoto, a renowned Buddhist chaplain from Japan.

Interfaith Chaplaincy for Rebuilding Community with Rev. Yozo Taniyama

On April 27, Rev. Yozo Taniyama of the Jodo Shin Otani Pure Land denomination led the group in a seminar on Interfaith Chaplaincy. Rev. Taniyama trained in hospital chaplaincy in the early 2000s in Japan at one of the few hospitals that provide such services. Since then, he has worked to develop Buddhist chaplaincy training programs in a deeply secular country that has banned religious professionals from serving in public facilities due to a narrow-minded interpretation of the separation of religion and state. In 2011, when the disaster struck, Rev. Taniyama moved back to the city of Sendai, on the very edge of the disaster area, where he had graduated from Tohoku University in 1994. At Tohoku University, he was able with a small group of comrades to establish the Department of Practical Religious Studies and an Interfaith Chaplaincy (rinsho-shukyo) training program. This program has specialized in training religious professionals of various faiths to provide healing ceremonies to commemorate those who passed in the disaster as well as to provide counselling and human connection at pop-up cafés in the relocation sites.

On April 27, Rev. Yozo Taniyama of the Jodo Shin Otani Pure Land denomination led the group in a seminar on Interfaith Chaplaincy. Rev. Taniyama trained in hospital chaplaincy in the early 2000s in Japan at one of the few hospitals that provide such services. Since then, he has worked to develop Buddhist chaplaincy training programs in a deeply secular country that has banned religious professionals from serving in public facilities due to a narrow-minded interpretation of the separation of religion and state. In 2011, when the disaster struck, Rev. Taniyama moved back to the city of Sendai, on the very edge of the disaster area, where he had graduated from Tohoku University in 1994. At Tohoku University, he was able with a small group of comrades to establish the Department of Practical Religious Studies and an Interfaith Chaplaincy (rinsho-shukyo) training program. This program has specialized in training religious professionals of various faiths to provide healing ceremonies to commemorate those who passed in the disaster as well as to provide counselling and human connection at pop-up cafés in the relocation sites.

Taniyama’s focus on interfaith chaplaincy comes from the need to accommodate not only various religious standpoints among the members of a wide variety of Shinto, Buddhist, Christian, and new religious groups in Japan but also non-religious standpoints and the barriers on any public religious work. This focus also comes from the influence of highly developed models of public chaplaincy in the United States, which requires chaplains to be able to attend to those of different religious backgrounds. In this way, Rev. Taniyama opened his talk by referring to the edicts of the great King Ashoka of India, who while being a devoted Buddhist also supported religious tolerance during his reign (268-232 BCE). From this standpoint, Rev. Taniyama further articulated the core principles of chaplaincy that: 1) no one shall be isolated; 2) we must be conscious of the public interest and being considerate of minorities; 3) religious cooperation, at least at the level of information sharing, is essential; 4) the beneficiaries must be regular citizens and never religious people and their institutions; 5) we must be considerate of confidentiality and privacy; and 6) we must develop short-term and long-term plans.

Building and fostering community and then connecting it to many other communities was also a major emphasis in Rev. Taniyama’s talk. Again, keeping with this ecumenical principle, chaplaincy services should be accessible to any citizen while also respecting local culture, tradition, and religion. An important corollary of this principle is the awareness by a chaplain of their own limitations and the limits of helping everyone, much less of “saving” anyone. In this way, the chaplain must always be prepared to request assistance from other professions, experts, or teams. Finally, it is essential to believe in the resilience of the care recipients themselves and their community. Rev. Taniyama said, “Let us believe that those receiving care are not helpless and pitiful human beings, but rather possess the strength, resilience, and recovery power to survive even in difficult circumstances”.

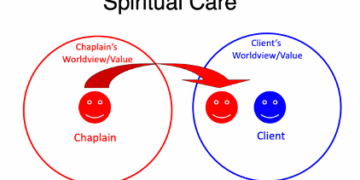

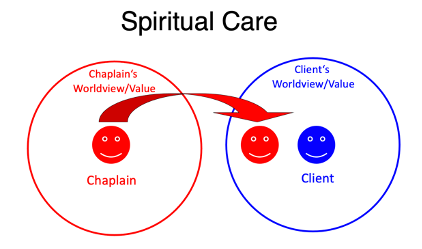

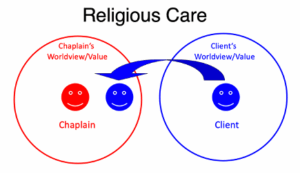

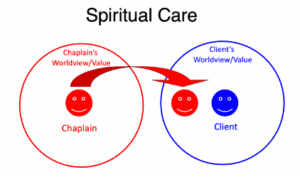

These basic principles led into Rev. Taniyama’s explanation of the differences between “religious care” and “spiritual care”. He first asked “Which fits your culture?” In modern secularized nations, like Japan, spiritual care that avoids reference to specific religious teachings and practices should be given priority. In more openly religious countries, like Iran and Taiwan, chaplains can provide non-compulsive religious care. Yet no matter the style chosen, forcing someone to come to the standpoint, awareness, or understanding of the chaplain is not appropriate. Rev. Taniyama instructs to start with listening. For a religious professional, talking is easy, but listening may be a new and difficult skill for them. Further, while anyone can listen silently, the attitude is more important than skill. For example, Rev. Taniyama instructs to let the person talk about what they want to talk about, even negative topics, like death and trauma. Accepting the person’s feelings and guiding them to not judge their experience nor compare with others is essential. On the other hand, forcing them to speak is also not appropriate and a space needs to be created, often first through silence, where they can freely express their emotions.

These are the basic principles of spiritual care. Religious care, if it is appropriate, can also be provide so as the chaplain’s beliefs are not imposed and they do not expect the victim to deepen their faith. Rituals can be a powerful tool for healing as well as meditation, listening to sutra chanting, and prayer, but Rev. Taniyama instructs to be mindful of the other person’s needs, decide when and what to do, and when not to do anything.

An offshoot of religious and spiritual care is grief care. This may involve creating a self-help group or support group. A facilitator of a self-help group shares the loss with the clients, while a support group is facilitated by a professional who may not have experienced the same loss as the participants. Such groups mirror how a community has the power to support all members within usual daily life, just through eating, talking, and sharing time without doing anything. This was one of the reasons for the success of the cafés created by Buddhist priests at the relocation sites in the months and years after the 2011 disaster, the last of which closed in 2019. In this way, Rev. Taniyama spoke about how in the immediate period after a disaster, survivors will speak about certain common themes but after a while their thoughts will change and diversify. Some people will take several years to begin speaking up. After some months, groups of those who have recovered and those who are still suffering from the disaster will emerge, and a divide will begin to form between them.

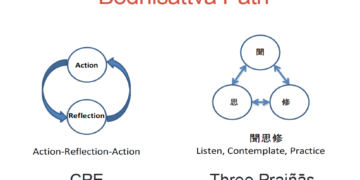

Rev. Taniyama said we should assume that a project to attend to disaster trauma will continue for 10 years or more. In this way, one needs to consider increasing the number of caregivers and expanding activities, or consider when and how to withdraw. This point leads into how to develop a chaplaincy training program. Rev. Taniyama explained, “If you help one person alone, you can help 10 people in a year. If you educate 10 students, you can help 100 people in a year. With 100 educators, it is possible to train 1,000 highly skilled care providers. With 100 educators, it is possible to train 10,000 moderately skilled care providers.” The former model corresponds to the Clinical Pastoral Education (CPE) system of professional chaplaincy system in the United States, while the latter is found in many hospices that rely on a cadre of volunteers and specifically the Cruse Bereavement Care system found in the United Kingdom. The Interfaith Chaplaincy (rinsho-shukyo) model which Taniyama helped develop has now been adopted by numerous Buddhist and religious based universities around Japan.

An essential final theme of Rev. Taniyama’s talk was the need for the chaplain and the caregiver to practice self-care and to take time off for their own well-being. There must be a priority put on the stability of care providers themselves. It can be important to share the day’s events with one’s colleagues but not with outsiders, especially due to the confidentiality of the work. After sharing, changing one’s mood is important, so that you do not bring stress home with you. While meditation and prayer can be effective, the caregiver should also live their same life as before. Finally, if you have some success with a method yourself, then it might be recommended to clients. In conclusion, Rev. Taniyama encouraged the seminar participants to “not be afraid to make corrections, not pursue perfection, and think while doing.”

Buddhist Chaplaincy for Post Traumatic Growth with Rev. Hitoshi Jin

On June 1st, the second seminar was led by Rev. Hitoshi Jin, Director of the Rinbutsuken Institute for Engaged Buddhism in Tokyo. Before the 2011 disaster, Rev. Jin had been building networks of priests and temples in Japan working on various issues with young people, such as school refusers, shut-ins, victims of cults and domestic violence, and so forth. After the disaster, he decided to build a comprehensive Buddhist Chaplaincy (rinnsho-bukkyo) training program based on aspects of the American model of Clinical Pastoral Education (CPE), Taiwanese Buddhist end-of-life care training, and engaged Buddhism practice in South and Southeast Asia.

Besides Rev. Jin’s experience in Japan, he has also worked on trauma relief in Nepal, where a massive earthquake struck on April 25, 2015 in which nearly 9,000 people lost their lives, with approximately 30% of the victims being children. In July and August of that year, Rev. Jin visited the Child Workers in Nepal Concerned Center (CWIN) headquarters in Kathmandu and conducted a trauma care workshop for staff members gathered from across the country. In Nepal, the concept of post-disaster trauma is not well established, and through lectures and workshops, all staff members gained a new understanding of trauma. They realized that appropriate trauma response can prevent the onset of PTSD.

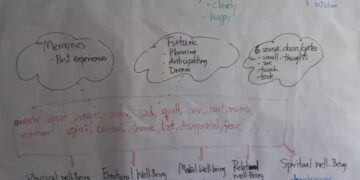

From these experiences, Rev. Jin began his talk emphasizing “restoring relationships”. He defined trauma as “a severing of trust between oneself and the outside world”. In daily life, one generally has the feeling of its potential, either trusting in oneself, like, “I guess there is something I can do,” or trusting in the world. However, when things fall apart, one may develop anxiety as, “What is going to happen now?” or despair as, “It’s impossible that this situation will get better.” In this way, the core characteristics of trauma are suspicion, isolation, and a sense of powerlessness.

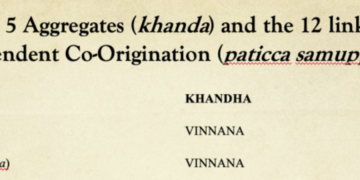

Frequently seen traumatic responses fall into the basic categories of: 1) the re-experience of trauma in which the memories of the traumatic experience return without any intention, such as nightmares, strong psychological pain and physical response, flashbacks, and especially in children, the repeated reappearance of shocking experiences while playing; 2) evasion and paralysis, which involves the avoidance of things that make one remember shocking events, like becoming catatonic, not recalling the important parts of an event, and having a feeling of estrangement from others. When one cannot think about the things that makes one happy, there is a general tendency towards social withdrawal; 3) hyper arousal, which involves insomnia (though in the case of children it can be severe drowsiness), difficulties concentrating, becoming frequently angry and annoyed, and becoming overly surprised by small matters; 4) other types traumatic responses may involve physical reactions, like headaches, gastro-intestinal disorders, hyperventilation, and heart palpitations.

Rev. Jin then went on to explain that there is a difference between a “reaction” and a “symptom” in trauma. In a reaction after a shocking experience, there is an emphasis on a “natural reaction”. In most cases, the strength and frequency together naturally decrease over time, though not necessarily disappearing. There becomes the possibility of a diagnosis of PTSD if the situation of this reaction continues over a month and becomes a marked obstacle in daily living. As such, there is a need for consultation with a specialist. The primary factors in the shift into PTSD is the severity of trauma, daily life stress, and the presence or absence of supportive people around the person. In trauma related to bereavement, such as that which comes from a sudden disaster, a grief process that is not usual occurs. There is invasive recollection and the continual struggle with questions like, “It seems I can’t avoid death. What will it be like for me at the end?”

While showing slides from the 2011 disaster in Japan, Rev. Jin also emphasized the importance of providing ways to express traumatic experiences in order to heal, called Narrative Therapy. While this form of therapy is considered to revolve around speaking and expressing oneself through telling one’s stories and experiences, there are also non-verbal ways of “narrative expression”. In Buddhism, there is the emphasis on the six sense doors (salayatana) through which we experience suffering but through which can also express that suffering. This kind of approach is particularly important with children who have yet to develop the cognitive and verbal skills to express their trauma through language. In the 1995 Hanshin earthquake around Osaka, “earthquake playing” as a way for kids to act out such disasters using lego or blocks or other such toys became an important therapeutic tool. After the 2011 disaster, Rev. Jin explained how they developed “tsunami playing” as a kind of Narrative Therapy. He said that they tried to support both adults and children to develop their own ways to express their trauma. Sometimes in this expression, violent words or actions come out, especially among very strict, adult men who repress themselves and may become alcoholic or suicidal.

From a Buddhist meditative background, Rev. Jin emphasized the importance of not evaluating while offering care for the victims of trauma. He explained that every person who has experienced trauma is different. Although we can say people have experienced the same disaster or incident, we cannot say they experienced the same trauma. There is a process to recovery, but the way of feeling sometimes differs. Every person differs in their process of recovery. Some may have a problem of speaking about the experience of trauma for quite a while. If there are no obstacles, the person will proceed to recovery. He urged to not evaluate them, simply sincerely provide them with what they need.

If a caregiver forces the victim to talk about their experiences or engages in unnecessary evaluation, the occurrence of a second trauma can occur. This will further disturb the process of recovery and sever the sense of trust in a victim, while strengthening their sense of isolation. Examples of such expressions by caregivers are: “Poor you.”; “Try harder.”; “There are people who have been through worse than you.”; “Try your best for those who have already died.”; “Please stop thinking about what has already passed.”; and “I understand how you feel.” For the victim, restoring trust in themselves and becoming empowered comes through connection and relationship. Such connection occurs because they feel unjudged and accepted for who they are as they are. They are able to discover the part of themselves that has been able to get things done so far as well as the part that can make choices and can receive help for the things they wish. They develop an increasing sense of “I can do this.”

In terms of cultivating an intimate interaction with a person in suffering rooted in deep listening, Rev. Jin has spoke of the Four Practices of the Bodhisattva (四摂法 shi-shobo). The fourth such practice of “working together” (Pali. samanattata 同時 doji) is especially important as it refers to working together by putting oneself on the same level as others and participating alongside them in activities. This can be further explained as putting oneself in the place of others and listening deeply without getting caught in one’s own view. The idea is to listen as Kannon Bodhisattva would and shift from “doing” to “being”. Rev. Jin notes that it is unusual for religious professionals in Japan to have received training in such deep listening, and especially for Buddhist priests, this can be a high hurdle to get over.

In this way, it is important for the caregiver through respectful listening to support to resilience and growth. Such resilience is an innate human quality. We all have a basic restorative power and adaptability to different environments. As such, Rev. Jin spoke of the shift from PTSD to PTG, that is, Post Traumatic Growth. He illustrated this to the audience, mostly Buddhists from the orthodox Theravada tradition, by pointing out the trauma that the Buddha himself must have experienced as a motherless son after his mother died in childbirth. This is an issue that is never brought up in the retelling of the Buddha’s life. However, Rev. Jin explained that he was surely traumatized by this experience but that he still could grow, and in many ways it may have been essential to his eventual enlightenment. He pointed out that “growth” has a specific meaning in Western psychology that differs from the Buddhist understanding that leads to enlightenment.

As a final advice for the audience, he encouraged them all, especially the monks, to practice the vipassana (insight) meditation tradition of their home country and try not to get lost in the ocean of emotions and feelings that comes with such caregiving work. This echoes the work of Buddhist chaplains around the world who are taught meditation is more important for them as caregivers than as a method for “curing” pateints and clients. Instead, for patients, Rev. Jin recommended the simpler practice of anapanasati (mindfulness with breathing), which he has used with terminal cancer patients and with children.

Conclusion

In conclusion, besides the specific foci of Rev. Taniyama’s and Rev. Jin’s talks, there were many common points in their talks, which reinforced themselves as essential points of learning for the participants:

- Non-judgement and total acceptance through deep listening as essential for the victim to rebuild trust and resilience as well as their own sustainable way to healing not imposed on them by a caregiving “expert” or religious “savoir”.

- The inherent potential for growth (a.k.a buddha-nature) through and beyond the trauma towards wholeness and perhaps even enlightenment as did the Buddha.

- The core need for caregivers to practice self-care through good daily life practices as well as religious practices, such as meditation, chanting, and ritual.

- Fostering connection and building community through an ecumenical spirit as essential to restoring the well-being of disaster victims.

The organizers and IBCC would like to express their deep gratitude to Rev. Taniyama and Rev. Jin for their time and energy (dana) to support those in Myanmar, and we look forward to further interactions and instruction from you both!

Written and edited by Jonathan S. Watts (IBCC Coordinator)