Dr. Prawate Tantipiwatanaskul (Thailand)

Given at the Public Symposium: Overcoming Contradictions in Psychotherapeutic & Spiritual Development in Buddhism. The Buddhadasa Indapanno Archives (BIA), Bangkok September 24 (Sunday), 2023

Hello, I’m Dr. Prawate, a psychiatrist. I’m interested in working with people’s minds to alleviate distress and nurture inner potential. I’ve been trying to learn different psychotherapy schools from the West during my 30 years in this field. Additionally, being born in Thailand, the land of Buddhism, I’ve started practicing Dhamma since I started my training as a psychiatrist. I was ordained as a Buddhist monk right after I finished my psychiatry training.

Over the years, I’ve experimented with combining psychotherapy and spiritual development, and today, we have a unique opportunity to discuss this topic. I’d like to thank our hosts for their support.

Psychotherapy, translated from English as “psychotherapy” in Thai, aims to help individuals return to normal functioning, transitioning from a negative state to a neutral one. Neutral means the same like “ordinary people” in society. It enables people to live, work, build relationships, and find happiness.

Developed in Western society over approximately 200 years, each psychotherapy school reflects its social context of that time. Each approach emphasizes distinct aspects of the how the mind works and offers various methods for treatment. Most schools at the beginning were influenced by medical model in its conception. Looking for abnormalities and diseases rather than health and positive functioning.

Psychotherapy presents itself as a science with systems to test for its efficacy. Research studies are conducted and published in journals, subject to reliable independent evaluation. It distances itself from religious teachings. Religion was perceived as driven by faith, not science.

In contrast, Buddhist Dhamma was discovered by an individual who attained enlightenment by himself. Its goal is to guide people for enlightenment. This fundamental difference sets them apart.

In last few decades, Western psychology and psychotherapy have seen significant shifts, partly due to technological advancements like brain activity measurement and a shift toward exploring happiness and human potential. Additionally, new approaches have emerged in addressing traumatic experiences in both adults and children.

Originally rooted in religion, spirituality aimed to answer life’s fundamental questions. Why we were born? How should we live? Where do we go after we die? As belief in religion wanes globally, many young generation declare that they have no religion. But a large number of people still have questions about lives. Current scholars define spirituality as seeking life’s meaning or value system, whether or not it’s tied to religion. This allows spiritual development without religious reliance.

Research also highlights the importance of spirituality for health and well-being. Even non-religious individuals ponder life’s questions, making spirituality a part of our lives, whether we acknowledge it or not.

Therefore, I believe effective psychotherapy should encompass the spiritual dimension, as every life problem presents an opportunity for spiritual growth and a search for meaning.

During Buddha’s time, individuals found Dhamma and attained certain level of enlightenment during life crises, like the story of Nang Kisā Gotami, known to Thai Buddhists.

My recent work confirms that during crises, people become more receptive to exploring life’s fundamental questions. When we consider spiritual development for those facing life problems, we wonder how it impacts their lives and how can we change those life challenges into opportunity for spiritual development.

What should be appropriate goals for spiritual development for people who don’t have much Dhamma practice or who want to go deep into Dhamma practice. Here are some I received from my students.

- To understand oneself, one’s life, Dhamma, and human nature.

- To increase inner peace, happiness, resilience, flexibility in letting go.

- To be more aware of their thoughts, feelings and less attach to them.

- To improve relationships with close ones.

- To be able to see oneself and others especially parents as human beings.

- And, for some, to venture into Dhamma teachings more deeply.

To be able to see oneself and others especially parents as human beings. And, for some, to venture into Dhamma teachings more deeply.

While we typically envision psychotherapy as a conversation between two people, I’ve found a combination of personal practice, group learning, mutual support, and private conversations to be most effective.

In my view, the psychotherapist’s role involves transforming life’s challenges into opportunities for spiritual growth. My approach is to work with my clients in one plus four areas. The first one is external circumstances and the four areas are their internal experiences.

The first one is to work at external circumstances and their daily lives. Each client has her own life context and stories. Our focus is on providing information and encouraging individuals to adjust their life systems. At this level, behavioral changes may be necessary to create conditions that facilitates internal growth.

Topics of discussion here include allocating time for basic self-care, physical activity, sleep hygiene, observing feelings and thoughts, mindfulness training, spending time in nature, time for reflection, reducing social media use, selecting brain and mind-friendly foods. Addressing these subjects according to individual needs.

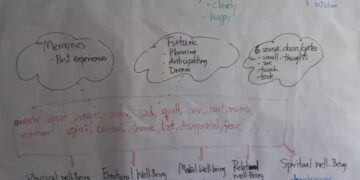

The internal aspect is divided into four areas, and I’ll discuss them one by one.

1. This first area involves inviting individuals to observe their inner experiences. As they do, most will notice their thoughts, which may manifest as internal dialogue or mental images, along with the emotions that arise in each moment.

Regular observation leads to at least three key realizations:

- We think most of the time and emotions are closely linked to thoughts.

- Emotions often stem from the thoughts we entertain.

- Recognizing and naming emotions can enhance control and management.

Emotions serve as a gateway to the deeper inner world, which we’ll explore in the second area.

By becoming aware of their thoughts and feelings, individuals gain essential insights into themselves, fostering personal growth and self-awareness. For those struggling to observe their own feelings and thoughts, a supportive, non-judgmental atmosphere with attentive listening can facilitate self-understanding.

Activities such as spending time in nature, light exercise, engaging in conversations with understanding friends, and recording thoughts and feelings can help people become more aware of their internal experiences, ultimately providing a clearer perspective on their issues.

The goal in this first area is to alter one’s relationship with thoughts and emotions, understanding that thoughts are not reality and can be observed objectively.

There is a term in Buddhist teachings: Thought is not truth. Thought is not myself.

With “Thought is not truth”. Practice to step back and observe one’s thoughts. Don’t believe the thoughts in your head. It’s not the truth. Most people are not aware of their own thoughts and they believe the thoughts that they are not aware of without having any means to test its truth.

With “Thought is not myself”. When we practice observing thoughts, we begin to see thoughts as a “cloud floating in the sky”. It’s not us. And we are the one who can observe thoughts in our minds.

2. The second area of internal experience to work with is a deeper internal experience.

This area is often more challenging to notice than the first. It encompasses memories, deep-seated beliefs, and expectations, particularly those rooted in childhood experiences. Two common methods for exploring this realm are:

- Questioning: By asking individuals to reflect on their beliefs or expectations, we are inviting them to look more deeply into their experiences. We can also ask about some of their experience in the past at appropriate time to bridge between current issues and past experiences. This requires specific skills.

- Mindful Embrace: Encouraging individuals to stay with their feelings and physical sensations that arise in the moment can help them connect with deeper aspects of their psyche. This method taps into the deeper layers of the brain beyond the usual thinking and language-processing areas. 4

An illustrative example involves a young man learning to manage his irritation by observing and embracing the sensations and emotions that arise in response to his academic challenges. This process led him to uncover deeper feelings of loneliness and unacceptance rooted in childhood.

When I invited him to connect with his irritation, he started to feel tension around his forehead at the area between his eyebrows. He then placed his right hand on his chest saying that he felt better connect to his feelings with this. After a moment, his irritation subsided and he began to experience sadness and fear. These emotions were linked to sensation around his chest. Images of his childhood experiences flushed in. They were moments that he was teased, bullied, with physical violence towards him when he was at his elementary school age. He felt so lonely and had no one. He also felt his rage towards his friends and himself. This awareness leaded to another awareness that he was not feel loved and he was yearning for acceptance. He also understood more on why he was so afraid of not being accepted by anyone around him.

Becoming aware of and accepting these suppressed emotions can facilitate healing, reducing the emotional charge they carry and preventing them from resurfacing in response to minor triggers.

Most people are not accustomed to delving into this inner space and tend to focus on solving external problems. However, recognizing the impact of inner reactions on daily suffering is essential, as individuals often struggle with their feelings and thoughts.

By acknowledging thoughts without judgment and understanding that they are not absolute truths, individuals can reduce their internal conflicts and become more attuned to their deeper experiences.

By exploring these first two areas, individuals can uncover the sources of their suffering, gain insights into their inner workings, and develop the ability to step back from rapid reactions and patterns that perpetuate life’s problems. This journey fosters self-awareness and empowers them to face life’s challenges with greater clarity and resilience.

3. The third area of internal experience encompasses the basic human needs that exist in everyone, including the need for safety, love, recognition, appreciation, value, inner peace, and freedom.

By regularly observing our inner experiences, we become aware of these needs and recognize that our reactions are often efforts to response to our basic human needs but most often we deal with outside world from our pattern learned from childhood experiences.

This awareness helps us understand that both our actions and the actions of others are often attempts to fulfill these fundamental needs.

People who effectively meet their needs tend to live harmoniously with others, while those who struggle to do so can create problems for themselves and others.

Understanding these needs in ourselves and others fosters compassion, a deep feeling within the heart, without the need for analytical thinking.

Recognizing imperfection and understanding the nature of humanity in oneself and others is crucial for personal growth and improved understanding of oneself and others. It can lead to better relationships, especially with parents, and help individuals become more discerning about societal trends and media influences.

There is a term in Buddhist teaching: we are friends of “common suffering: birth, getting old, get sick, and death”.

4. The fourth area involves moments of solitude and stillness, where individuals let go of thoughts and feelings from the first area. And silence reactions from childhood experiences. In this space, they focus on their breath, body, and the surrounding nature. They perceive experiences through their senses, connect with their surroundings, experience inner calm, and connect with themselves on a deeper level.

This experience allows them to see their own experiences from a different perspective, fostering increased awareness and faster detachment from automatic reactions.

Meditation is a well-known method to enter this space, but for those who still dislike meditation, practices such as spending time in nature, light exercises, yoga, Tai Chi, and Qigong can be effective. Regular practice in this space helps individuals connect with their deeper selves and better navigate their experiences in the first three areas.

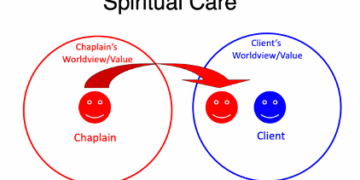

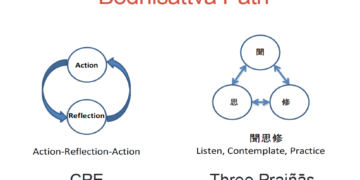

In my psychotherapy work, I address all four areas of inner experience and also consider external factors like behavior and lifestyle. While I have learned from Western psychotherapeutic techniques and appreciate their intellectual heritage, I believe psychotherapy often serves as a gateway to spiritual growth.

However, psychotherapy may only lead individuals to a certain level of spiritual development. Some of those who consult with me express a desire to ordain or deepen their Dhamma practice. I see my self as a messenger guiding them to find their own spiritual path. Generally, I don’t teachings Dhamma myself.

Experiencing all four areas is a part of inner development and serves as a link between mental care and spiritual growth. The extent to which the treatment process aids in spiritual development depends on individual needs and interests, as well as the therapist’s understanding and experience.

If we are going to bring Dhamma directly into any healing process. I propose 5 points to consider.

1. Avoid giving advice or directives in a teaching manner and focus on helping individuals learn from their own direct experiences within each of the four areas.

2. Recognize the limitations of spoken language and understand that emotional memories are deeply stored in the brain. Work primarily with sensations in the body and emotional experiences. Talking only has very limited impact.

3. Encourage practical learning experiences in each area, including creating a space of inner peace, connecting with nature, and exploring the important questions of life in a supportive group setting.

4. Share information about useful principles at the right time, when individuals are ready to recognize and learn from it.

5. Be cautious about assuming that mindfulness practice is universally beneficial, as intensive practice, especially for those with childhood trauma, can have negative effects, as it can trigger those memories and cause a number of symptoms that may not recognized by mindfulness teachers.