To Psychotherapy and Spiritual Development

By Dr. Prawate Tantipiwatanaskul (Thailand)

1. Rev. Masazumi Okano (Japan)

2. Rev. Elaine Yuen (USA)

3. Rev. Gustav Ericsson (Sweden)

Comments by Rev. Masazumi Okano

Kodo Kyodan Buddhist Fellowship, Japan

The two principles of Buddhist practice are:

1. Refrain from harming others

2. Benefit others

These practices are fundamental to both the ordained and the lay practitioners of Buddhism. The ultimate goal of Buddhism is to attain enlightenment. For lay Buddhists, it would be beneficial to start with being engaged in one’s spiritual development.

Dr. Prawate has pointed out these key aspects of spiritual development in his talk today and I agree with his ideas.

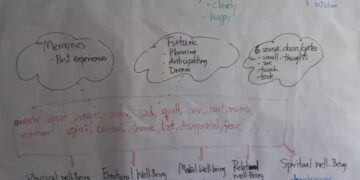

To understand oneself, one’s life, Dhamma, and human nature.

To increase inner peace, happiness, resilience, flexibility in letting go.

To be more aware of their thoughts, feelings and less attach to them.

To improve relationships with close ones.

To be able to see oneself and others especially parents as human beings. And, for some, to venture into Dhamma teachings more deeply.

Let me discuss this topic from a Buddhist perspective. In my opinion, Buddhist spiritual development is based on practicing the two principles of “refraining from harming others” and to “benefit others”. It seems easy to practice these two principles but in reality it is very difficult.

Refraining from Harming Others

Refraining from harming others means not to be engaged intentionally in harmful physical, verbal, or mental actions.

• Refraining from harmful physical actions may seem to be easier, however, we should be aware that one can indirectly bring harm to others by misleading them, putting them under stressful situations, or taking away or not giving them what they really need, etc.

• Harmful verbal actions include, deceiving others, lying to people in order to benefit yourself, or speaking badly about others, etc.

• Harmful mental actions include bearing such thoughts and emotions as malice, hatred, jealousy, and envy, etc.

In my opinion, it would be easier to start withrefraining from harmful physical and verbal actions because one can be more aware of them. Being constantly aware of one’s mental actions would be more difficult. But it is very important to try to do so because physical and verbal actions have roots in mental actions. Dr. Prawate has taught us how to be aware of our inner experiences.

Let me discuss why refraining from harmful actions is important. It is because intentionally harming others would disturb our inner peace. Whatever the reason, the actions with the intent to harm others would not bring us happiness. It may create a chain reaction of tit-for-tat which will end up in perpetual human relationship problems.

Even if we are under threat from others, we could try to defend ourselves without bearing malice towards the attacker. That way, it would be easier for us to stop the vicious cycle of retaliation.

In fact, understanding truly beneficial ways to protect ourselves is important. Keeping our physical and mental well-being is necessary and fulfilling our basic needs is essential. Protecting ourselves in order to meet these needs is very important.

However, we should become aware of what we are trying to protect. What we are trying to protect may not be worthwhile or it may in fact be a cause of our own suffering.

For example, overprotecting our self-image may cause us anxiety, anger, jealousy, and envy. Self-image is something that we have created in our mind which is a very simple and biased image of ourselves. We are much larger and more complex and fluid than that. But we become so attached to it, we would do anything to protect it while our inner peace may be disturbed and our relationships may be destroyed.

Benefitting Others

Let me discuss next about the second Buddhist practice of benefiting others. Buddhism teaches us that we do not exist independently from one another. We are part of a large network of living beings within which each depend upon on one another. We are not separate from others. Others constantly influence my physical, mental, and emotional states. And at the same time, I constantly influence the physical, mental and emotional states of the people around me.

In our daily lives, we know that we depend onothers for our food, transportation, infrastructure, etc. But often we forget about this fact and behave as if we live by ourselves. My needs, my feelings, my self-image, etc., become the only important things while the needs and feelings of others are completely ignored. Here too, often the urge for self-protection turns out to be the cause for these selfish drives. We feel so strongly that we have toprotect ourselves, we would have no consideration for others.

Being in a selfish mode keeps us in a unpeaceful and often painful state of mind. In this state of mind, we often feel greedy, anxious, unsatisfied, and threatened. And we feel cut off from the world around us. We feel like using others to fulfil our needs and when others seem to threaten us we would do anything to get rid of them.

To benefit others is a practice to step out of this selfish mode. It is to be concerned about others’ well-being. It is to understand the joys and pains that others experience and to empathize with them.

The practice of benefiting others can be a simple practice. We just have to set aside our selfish drive. Even small gestures such as smiling and saying kind words can benefit others.

However, in order to truly benefit someone, we need to understand the other person’s thinking, feelings, and needs. Trying to understand the other person is the key to this practice.

But this is not always easy especially in the family situation. We often have fixed ideas of our family. We think we know why the family behaves in certain ways and we think we know what that person thinks and how the person feels.

But the assumptions about our family are often not accurate. We often misunderstand our family completely. But we think we know them well. For the practice of benefiting others, we should start with the people who are close to us such as our family. We should try to understand our family each moment with a fresh attitude rather than reacting automatically with the same pattern. Always reacting in the same way means that weare attached to the fixed ideas about our family.

Buddhism teaches us that each of us is very complex and ever-changing. If we want to benefit others, we need to remember this fact.

Buddhism, at least in the Buddhism I follow, thinks that the negative thoughts and emotions are like clouds of dust. Although they may be very sticky and difficult to get rid of, if we keep practicing, we would be able to find our innate wisdom and compassion underneath them.

Comments by Rev. Elaine Yuen

Naropa University, USA (retired)

I’m very happy to be here. I’m intrigued by Dr Prawate’s comments, they resonate with me deeply. I come from the United States, where Buddhism has entered a large swath of our society through psychology. I myself am a Tibetan Buddhist practitioner and teacher. So I’m very interested in our conversation, and want to comment on developments in the west of Buddhist (spiritual) practice and development. I also want to describe how it has applied, from my perspective as a spiritual caregiver (chaplain) and teacher.

A Buddhist Perspective on Mind

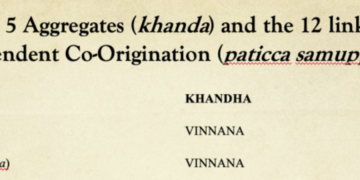

The mind is naturally clear and knowing, and mind is very powerful – just look at the art, science and creativity that humankind has produced. Mind is also very untamed, there is the traditional Buddhist image of a wild ox, trampling on a carefully tended garden. So our personal psychology – and our relationships suffer from this wild mind, wild ox. This is the First Noble Truth – of suffering, that experience is out of balance, like a loose cart axle.

The Buddha then went on to describe how our grasping creates this suffering, and ultimately describes a path to liberation that includes understanding (prajna), meditation (samadhi), and behavioral ethics (sila).

The example of the Buddha as a human being who achieved liberation can be instructive for our time. When he became enlightened, he touched the earth after being beset by his demons – maras – and proclaimed “the earth is my witness.” We, as practicing Buddhists, are likewise encouraged to touch THIS earth – This phenomenal world of 2023 – with its anxieties and depression, social unrest, and environmental challenge.

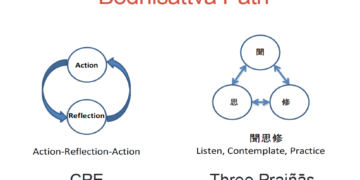

Our spiritual development – of training and taming the wild ox – is one that encourages connection this connection – this touching the earth. In meditation practice we connect authentically with our personal and environmental awareness – and how it plays out in a larger social context.

We train the mind – through shamatha mediation – the development of peace; as well as encourage vipashyana – the development of awareness. It is said these are like 2 wings of a bird – to live a full life both are needed. Dr Prawate has beautifully described this process.

The Many Applications of This View

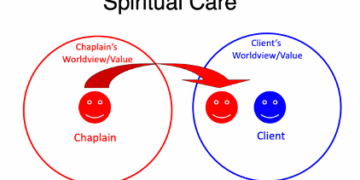

I would like to talk about my experience as a Buddhist interfaith chaplain. The path of the chaplain is one of a spiritual caregiver, learning to be present with the sufferings of others. To hear the cries of the world. So it is one of listening, witnessing and if appropriate – offering compassion in its myriad forms.

I like to tell my students that it is listening to our inner voices, and bringing some kind of attunement between our “inner Buddha – inner peace” and offering this to others – it could be a prayer, a gesture, a longer conversation.

My Buddhist understanding – and coming to terms with – my own suffering and practices – support me in bearing witness to the sufferings of others. There is an authentic connection that acknowledges our collective humanity and allows one to be fully present in our world, to touch our world genuinely.

The offering of compassion could take different forms – it is a question of “what is life giving to this person in front of me?” And “what is life limiting?” – similar to some of the things Dr Prawate spoke of.

Sometimes a physical gesture – like a hug, touching the shoulder, or joining of hands around the hospital bed – brings in a wholeness, completion to an environment.

Sometimes it is a verbal invocation – a prayer, perhaps stitched together on the spot from our conversation – brings a sense of peace and understanding.

And sometimes it is a conversation that unearths difficulties around social and environmental justice, practical difficulties

This discrimination of what is helpful in a given situation is supported by vipashyana – an awareness that develops side by side with the peacefulness – shamatha. Meditation practice habituates and tames our mind so we are able to notice – within ourselves as well as with others – what gestures of body, speech and mind support harmonization and attunement.

This is how we might care – for ourselves as well as for others. Buddhism and psychology have in common this aspiration and practical approaches.

Comments by Rev. Gustav Ericsson

Lutheran Church of Sweden

Dr. Prawate, what a joy it is to listen to your presentation and to get to know you! I am not a doctor, but, like you, I have been very interested in research on how the body and mind works, and still I chose to ordain in a religious tradition. Which I am very happy for today! I wonder why spirituality was not enough for you, and what ordaining as a Buddhist monk has added, opened, or touched, that non-religious spirituality or academic research did not fulfill in the same way? In what ways, if any, did it add flesh to the bones?

I was nodding throughout your lecture, appreciating every part of it, and how it comes from your loving-kindness for others, and especially for those in distress. There is one more part of the religious life, however, that has been a central heart-matter to me, that I would like to add to the picture, and ask for your comments. This central part is when religious life and practice lets go of all instrumentality. On the cross, Jesus says: ”Into your hands, Lord, I commit my spirit.” Jesus taught his diciples the practice of dying from oneself. And often in the church we pray to surrender any results of our practice into God’s hands. I believe religion can help save me from being completely twisted in to my own self, like a knot. It can help me at times to let go of instrumentality where there is an ”I” that has something to gain. To help me breathe like that. To me, these moments has been indescribably meaningful. Transforming, allthough in my case very small glimpses. I’m not sure what to call this space of non-instrumentality, or, perhaps, no separate gaining self, but I have come to appreciate it as the other wing of the bird. What do you think, is there a point in councelling where it is time to let go of one’s ideas of self and one’s own suffering? In Leonard Cohen’s words, ”to let go of my own masterpiece, and sink into the real masterpiece?”

I feel aligned with your concluding five principles. What an inspiring summary of important guiding stars in religious chaplaincy! My only comment is that, in my experience, the importance of spoken language has been a matter of quite broad individual variation. To what extent have you found individual variations regarding these five principles?

One final question comes from my appreciation of C.G. Jung. There is an image of one of his letters circulating on social media where he writes:

”I can only tell you one thing: that you should not set out to seek happiness for yourself. This would be a straight way to unhappiness. You better ask where and how you could be useful to whom. Happiness is not a thing one seeks. It comes to you as a reward for efforts.”

I wonder if you have any thoughts or comments regarding psychotheraphy or religion/spirituality, and how it relates to serving others?

From the Public Symposium “Overcoming Contradictions in Psychotherapeutic & Spiritual Development in Buddhism” @ The Buddhadasa Indapanno Archives (BIA), Bangkok. September 24 (Sunday), 2023 14:00-17:30